|

303rd BG Original Crew 358th Oxrider Crew George J. Oxrider, Pilot |

Personnel

Mission Reports

GEORGE J. OXRIDER CREW - 358th BS

B-17F Werewolf #41-24606 (VK-H)

(original crew assigned 358BS: 15 Sep 1942 - photo: Prestwick, Scotland, 13 Oct 1942)

(Back Row) Capt George J. Oxrider (P), 2Lt Donald W. Hurlburt (CP),

1Lt Donald L. Grant (N), 2Lt Thomas R. Thomas (B)

(Front Row)

T/Sgt Frederick B. Ziemer (E),

T/Sgt Everett A. Dasher (R),

S/Sgt James K. Sadler (TG),

Sgt Clifton R. Finscher (BTG)(POW),

S/Sgt Samuel P. Maxwell (RWG)

Original crewmen who flew B-17F Werewolf from the USA arriving Molesworth on 24 Oct 1942

(crewmen are not in order)

Crewman not in Photo:

S/Sgt George F. Hall (LWG)(KIA) - Did not fly to England with the rest of his crew.

2Lt Leon W. Blythe, (Passenger on overseas flight) - Assistant 303rd Operations Officer

Twenty dispatched (18 credited) missions flown by Capt George J. Oxrider:

1 (17 Nov 1942), 5, 8, 10, 11, 12(A), 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22(A), 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33 (4 May 1943)

(A) Non-credited aborted missions:

- #12, 27 Jan 1943, in B-17F #41-24541 Spook. Crew had a harrowing experience in keeping with

the B-17's name. A life raft, released by the vibration from the firing of the Top Turret by T/Sgt

Ziemer, struck the Left Waist Gunner, Sgt Raesley. The Left waist gun went wild, shooting holes

in the side of the B-17 and wounding Tail Gunner Sgt Sadler. Sgt Sadler received two bullet

holes (not serious) in his right buttock and was hospitalized. These events caused Pilot Lt

Oxrider, to return home when ten miles over the English Channel (Flight time 1 Hr 12 Min).

- #22, 12 March 1943,. in B-17F 42-5439 Pappy aka Good Enuf. The flying suit of Tail Gunner, S/Sgt

Sadler, went out and his feet became frostbitten (Flight time 2 Hrs 01 Min).

For Mission dates, targets and Mission Reports, see Combat Missions.

- 41-24606 Werewolf (358BS) VK-H - Missions 1, 8, 11

- 41-24582 One O'Clock Jump (358BS) VK-G - Mission 2

- 41-24577 Hell's Angels (358BS) VK-F - Mission 10

- 41-24541 Spook (358BS) VK-G - Mission 12 (A)

- 42-5264 Yankee Doodle Dandy (358BS) VK-J - Missions 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33

- 42-5430 Pappy aka Good Enuf (359BS) BN-V - Mission 22(A)

- 42-56482 Cat-O-Nine Tails (359BS) BN-W - Mission 25

- Capt George J. Oxrider (P) - All missions except #10 flown as First Pilot. Mission #10 flown as

CoPilot with Capt Irl L. Baldwin (P). Did not complete his 25 mission combat tour. Last mission

(33) on 4 May 1943. Transferred to Zone of Interior on 11 May 1943. Promoted to Major and

became Commanding Officer of the 728th BS(H), 452nd BG(H), later the 728th Airlift Sq., from,

9 July to Sept 1943 at Rapid City AAB, SD. Was awarded the British Distinguished Flying Cross

on 29 Jan 1943 following aborted mission #12.

Major Oxrider was Killed in Action over Denmark with the 452nd BG on 9 April 1944. He was flying as CoPilot on that mission. He is buried in the Ardennes American Cemetery. More information is available here.

- 2Lt Donald W. Hurlburt (CP) - Flew on 19 Dispatched (17 credited all Capt Oxrider missions

(All missions except for mission #10). Flew on 8 credited missions with 1Lt Robert L. O'Connor

(P) - (Missions 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43). Completed 25 mission combat tour on 22 June 1943

(Mission 43). Was Killed on Oct 1, 1943 when the aircraft he was flying crashed on takeoff

during a local mission at Eglin Field, Florida. Hurlburt Field, Florida, near Ft. Walton Beach, was named

after him. His portrait hangs in the Officers Club at that base.

- 1Lt Donald L. Grant (N) - Flew on all of the 20 dispatched (18 credited) missions of Capt Oxrider.

and on 8 missions with other Pilots: 1Lt Robert L. O'Connor (34, 35, 38, 39, 40); Three other

Pilots (7, 9, 13). Completed his 25 mission combat tour on 29 May 1943 (mission 40).

After completing his overseas tour, Grant rotated back to the United States and became a Navigator Training Instructor. He did not like it very much, and it bothered him knowing that many men he trained would be killed. He volunteered to go back for a second combat tour and was assigned to the 484th BG. 1Lt Grant was killed in action on 9 June 1944 on a mission to Munich, Germany. His aircraft was shot down over the Adriatic Sea and his body was never recovered. He is listed on the Tablets of Missing at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery.

- 2Lt Thomas R. Thomas (B) - Flew on 2 dispatched (1 credited mission with Capt Oxrider

[Missions 1, 12(A)]

- T/Sgt Frederick B. Ziemer (E) - Flew on all of the 20 dispatched (18 credited) missions of Capt

Oxrider. Flew on 7 credited missions with other Pilots: With Capt Carl L. Morales (Mission 4 as a

Gunner); With 2Lt Robert L. O'Connor (Missions 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41). Completed his 25 mission

combat tour on 11 June 1943 (Mission 41).

- T/Sgt Everett A. Dasher (R) - Flew on 19 Dispatched (17 credited missions of Capt Oxrider (All

missions except for mission #8). Flew on 4 credited missions with other Pilots: With 2Lt Carl M.

Morales (Mission 4); With 2Lt Robert L. O'Connor (Missions 34, 35, 38). Completed 22 credited

missions on 19 May 1943 (Mission 38). Became a Protestant Minister following WWII and

served as the 303rd BGA Protestant Chaplain from 1994 to 2001.

- Sgt Clifton R. Finscher (BTG)(POW) - Flew on 2 credited missions with Capt Oxrider (1, 5) and

2 credited missions with other Pilots: Lt James B. Clark (Mission 7) and 1Lt Oran T. O'Connor

(Mission 11. Became a POW on mission #11, 23 Jan 1843 in B-17F 41-24580 Hellcat. B-17 was

ditched in the Bay of Biscay (8 POWs and 2 Evadees- MACR 15473)

- S/Sgt Samuel P. Maxwell (RWG) - Flew on 19 dispatched (18 credited) missions with Capt Oxrider (All missions except aborted mission #12). Flew on 7 credited missions with other Pilots:

1Lt Joseph H. Haas (Mission 4); 1Lt Robert Nolan (Mission 6); 2Lt Robert L. O'Connor (Missions

34, 35, 38, 39, 40). Completed 25 mission combat tour on 29 May 1943 (Mission 40).

- S/Sgt George F. Hall (LWG)(KIA) - Flew on 1 credited mission with Capt Oxrider (Mission 1).

Flew on 5 dispatched (5 credited) missions with other Pilots: With Capt Irl E. Baldwin (3); With

1Lt James B. Clark (4, 6(A), 7, 9). Was Killed on 3 Jan 1943 (Mission 9). 1Lt Clark ditched his

B-17F 41-24526 Leapin Liz in the Bay of Biscay (All ten crewmen were Killed - MACR 7650).

- S/Sgt James K. Sadler (TG) - Flew on 14 dispatched (12 credited) missions with Capt Oxrider (Missions 1, 8, 10, 11, 12(A), 22(A), 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33). Flow on 11 credited missions with other Pilots: Maj Wurzbach (P), Lt Dunnica (CP) - Lead crew mission 4); 2Lt Robert L. O'Connor (Missions 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 47). Completed his 25 mission combat tour on 29 June 1943 (Mission 47).

- 2Lt Earl C. Steele (B) - Replaced 2Lt Thomas. Flew on 14 Dispatched (13 credited missions with

Capt Oxrider (8, 11, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22(A), 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33). Flew on 13 missions with other Pilots:

1Lt Joseph E. Haas (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 10); 2Lt Robert H. O'Connor (34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42). Completed

25 mission combat tour on 13 June 1943 (Mission 48).

- S/Sgt Robert H. Smith (BTG) - Replaced Sgt Finscher. Flew on 21 Dispatched (20 Credited)

missions with Capt Oxrider (All Oxrider missions except 1, 5, 8, 10, 11, 12(A). Flew on 7 credited

missions with other Pilots: 1Lt Joseph E. Haas (Missions 7, 10); 2Lt Robert H. O'Connor

(Missions 34, 35, 38, 39, 40). Completed his 25 mission combat tour on 22 June 1943 (Mission 40).

- S/Sgt Theodore C. Heaps (LWG) - Replaced S/Sgt Hall. Flew on 18 dispatched (17 credited missions with Capt Oxrider (All Oxrider missions except 1, 2, 22(A) ). Flew on 9 dispatched (8 credited missions with other Pilots: 1Lt Robert J. Nolan (14(A)]; 2Lt Robert L. O'Connor (34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43). Completed his 25 mission combat tour on 22 June 1943 (Mission 43).

- January 23, 1943, Mission 11 (Aborted) to Lorient, France in B-17F 41-24606 Werewolf

Lt Oxrider ordered his nine crewmen to bail out over the south coast of England after limping

back to England with only one engine operating. He landed Werewolf on a rugby field on the

grounds of a mental hospital at Dawlish in Devon England. It was originally thought to be

beyond repair. The VIII Service Command decided to repair the B-17 and fly it out. They changed

three engines and cleared trees, walls and hedges to make a 2,500 foot runway. The take-off was

successful and it was flown to Honington Air Depot for further major repairs. On 22 April 1943,

after repairs had been completed, Werewolf was transferred to the 401st BS/91st BG(H) where it

remained for two months after which it was reassigned to the 1st Combat Crew Replacement

Center at Bovingdon. There were no bail-out or landing injuries to the Oxrider crewmen.

- March 31 1943, Mission 27, to Rotterdam, Neth in 42-5264 Yankee Doodle Dandy.

The formation was flying through heavy clouds. The Oxrider crew was flying in the Low

Squadron as "Tail-end Charlie" T/Sgt Ziemer (E) was standing behind the CoPilot watching the

B-17 on the right - 1Lt J.R. Dunn (P) in 41-29573 Two Beauts. T/Sgt Ziemer saw a wing of

B-17 42-24599 Ooold Soljer, Piloted by 1Lt Keith O. Bartlett come through the window of

Two Beauts pushing a man out the window.. T/Sgt Ziemer yelled at Lt Oxrider (P) who pushed

his controls forward as the two B-17s who had collided went over the top of Yankee Doodle

Dandy. A three plane collision was avoid by only a few feet. They got back to their mission

formation at the European Coast.

- May 19, 1943, Mission 38, to Kiel Germany. B-17 Pilot 2Lt Robert S. O'Conner, who was flying with members of the Oxrider Crew, had left the formation over the North Sea when out of range of German fighters to rush back his Radio Operator, T/Sgt Everett A. Dasher, peace-time school teacher of Georgia, who had a serious chest wound. When he was approaching Molesworth 2Lt O'Connor feathered one of his engines and landed with three operating. Soon afterwards the rest of the 303rd formation approached Molesworth and landed.

B-17F #41-24606 Werewolf (358th BS) VK-H after the landing by Lt George Oxrider on a rugby field on the grounds of a mental hospital at Dawlish in Devon, England. The B-17 was returning from a mission to Lorient, France on 23 January 1943.

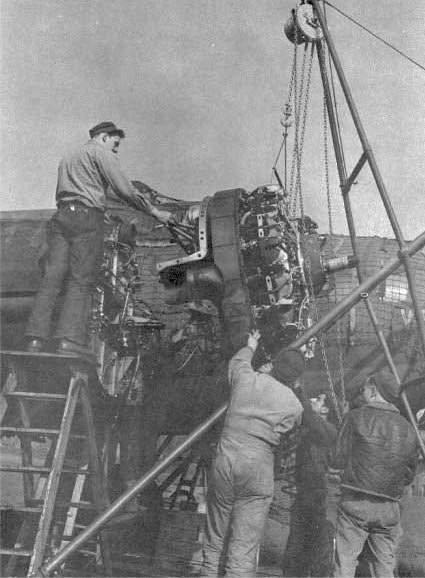

Members of a VIII Service Command Mobil Repair Unit based at Dawlish, Devon hoisting a new #3 engine into place on B-17F Werewolf following her emergency landing on the grounds of a mental hospital at Dawlish by 1Lt George J. Oxrider.

on Grounds of British Mental Hospital

By Iris Drinkwater, Military Historian

(from Hell's Angels Newsletter, Nov 1999 and Feb 2000)

On the outskirts of the south coast seaside town of Dawlish, in the county of Devon, England, a number of boys were playing football during the afternoon of January 23rd, 1943, when suddenly they heard the sound of an approaching aircraft. That in itself was no great surprise to the boys, who were used to hearing, or to seeing, friendly aircraft returning from bombing missions to France, and as no siren had sounded out a warning, they knew it had to be a 'Friendly'. But even to the untrained ears of the boys, the plane was producing a different sound than others they had heard. There was no steady roar from four engines, and it seemed much closer to them than usual. Then suddenly it came into sight, wheels down and little higher than the hedge surrounding their football pitch, with only one of its four engines running. As they all ran out to the centre of the field to get a better view, it didn't occur to them the pilot was trying to land his crippled plane on their pitch. As the plane headed straight for them, and would surely have ploughed right through them, the pilot lifted it high enough to pass over their heads, then down it came again, roaring off through the fence, and on towards the grounds of the nearby Langdon mental hospital. They dashed off in pursuit.

Within the grounds of the enormous hospital, it had been a day like any other day. Severely disturbed patients lived in secure areas, surrounded by high fencing, but the others were permitted to work on growing fruit and vegetables, under the close supervision of ancillary workers. The area used for growing cabbages had been ploughed in preparation for planting, and work was in progress in other areas, including the farm shop, when to everyone's amazement, a huge plane came crashing through fencing, and on towards the cabbage patch. Then just as it seemed it must crash into an oak tree, which was amongst the trees which lined the wall at the end of the cabbage patch, the wheels sank into the soft earth, and the plane came to a standstill. From all directions, doctors, nurses, patients and ancillary workers rushed out to greet their unexpected visitors. Expecting to see a number of airmen climb from the plane, they were surprised when just the pilot emerged. He was immediately surrounded by a mix-mash of humanity, all talking and asking questions: "Where were the rest of the crew?" "Where had he come from?" "Why did he land here?" And then, of course, because he was in England, he was offered a cup of tea.

Meanwhile, west of Dawlish, on the outskirts of the bleak moorland known as Dartmoor, a girl was riding her pony, and several young boys were roaming. In winter especially, Dartmoor is one of the most inhospitable places in England, which is why a prison was built there. Dartmoor covers an area in excess of 60 square miles. There are mountainous hills, known as Tors, and man-eating bogs. As if that were not enough for any would-be parachutists during WWII, American and British Battalions had established gunnery ranges in the more remote areas, which were strictly off limits to the general public. Single track roads are the only means of gaining access to isolated farms and moorland towns and villages such as Princetown, and Widdecombe-in-the-Moor. Few venture onto the moor in winter, unless they know enough about the place to find their way off it again. In winter, the fog rolls in quickly and without prior warning, hiding all landmarks. Get stuck on the moor in a winter's fog, and if the bogs don't get you, then hypothermia will, with the chances of survival being as bleak as the moor itself. And so it was, that on January 23rd, 1943, a girl rode her pony, and the boys roamed.

Most English children had become conditioned to wartime, and there was a deep seated hatred for an enemy who had caused so much destruction, and who was depriving everyone in England of even the most basic of commodities such as food and clothing. Parents of children everywhere were constantly reminding them of the danger of enemy airmen, who could be landing by parachute, for whatever reason. They were warned not to approach them under any circumstances. But, with the bravado of children, they heeded the warnings, but secretly vowed that they would not be intimidated. After all, they were English, and weren't the English determined not to be intimidated by their enemies?

So that when a lone parachutist was seen descending close to where the boys were, the boys rushed over, determined to deal with their hated 'enemy' as soon as he fell to the ground. The girl, meanwhile, who was older than the boys, also disregarded the warnings of her parents, and, instead, instinctively, knew that this was someone who would need help. She quickly rode over to where the boy had drawn his penknife, and found herself confronted by a young American airman, scarcely older than herself, who was more than a little frightened by his ordeal of a first time parachute jump. He was shivering in the cold January day, and so, without more ado, the girl leapt off her pony, and insisted he ride, whilst she led the pony back to the warmth of her parents farm, where she was to learn that he was T/Sgt. Everett S. Dasher, the Radio Operator from a B-17F, serial number 41-24606, nicknamed WEREWOLF, on this day one of 21 B-17's despatched from their base at Molesworth, England, to bomb the port of Lorient, France.

Although the young airman did not know it at the time, the rest of his crew had also survived their enforced departure from their plane, whilst his pilot, who had promised to follow his crew out of the aircraft, could find no place where he could abandon the plane without fear of it crashing and causing death and destruction on the ground, and so he had stayed with it, and landed it alone, wheels down, using the one serviceable engine. Last to leave the plane had been the Co-Pilot, Donald W. Hurlburt, who had refused to go until Pilot George Oxrider promised to follow him.

As the crew descended on their parachutes towards the inhospitable Dartmoor, their problems became obvious. "It's tough enough to have to bail out of a Flying Fortress, but it's sadder by far," according to Lt's Donald Hurlburt and Donald Grant, "to find yourself hurtling into an American Artillery range where your own guys are lobbing 155mm howitzer stuff all over the place." But they needn't have worried, for the men of the Battery, commanded by Capt. Cecil Harvey, had seen the airmen leave the plane, float down and disappear behind a neighbouring hill. They sent out a Jeep to pick them up. The Jeep got stuck in deep mud, but eventually accomplished it's mission. It was the first time that either flyer had jumped. Neither was injured, but both were slightly nervous and shaken up.

Top Turret gunner, Fred Ziemer, parachuted into the arms of a farmer who, convinced he had captured a German parachutist, marched Ziemer off to a policeman. Right Waist gunner, Samuel Maxwell, landed on a mountainside in his bare feet. The snap of the parachute as it opened, had thrown his shoes off.

Ball Turret gunner, Bob Smith, came down in the middle of a flock of sheep, scattering wool all over the countryside. The remainder of the crew wandered over the uninhabited moor for hours before being found by British Home Guards. Many conflicting stories about the pilot who landed his plane on one engine, appeared in the press, until George Oxrider told his story. They had flown through cloud at an altitude in excess of 20,000 feet, and all but three of their guns had frozen up. The only guns left operating were one waist gun, the nose gun and the top turret gun. Then, before they reached the target area, flak knocked out the cylinder in their # I engine. The manifold pressure immediately dropped ten inches, making it impossible to keep up with the rest of the formation.

Said Pilot George Oxrider; "I cut the corner, planning to rejoin them on the flight back, and ran into a mess of FW 190's. They got the #4 motor and then the #3 motor, setting them both afire. The FW's stayed with us until we reached the Channel, and then they had to turn back because they were out of ammunition." By the time they were within 50 miles of the south coast of England, the fires were under control, and the props on #'s 3 and 4 engines feathered. But on reaching the coast, #1 engine gave out, leaving them with just one engine running. George checked with his navigator on what airfields were within a reasonable distance, but there was only one hole in the overcast. By now they were flying at an altitude of 9,000 feet and the altimeter was slowly dropping. Finally came the order for the crew to stand by for bailing out, but they thought their pilot was kidding. They didn't know what bad shape they were in. One by one they jumped until, with the exception of the navigator, the co-pilot and the pilot, all were gone from the aircraft. The navigator had discovered, just in time, that he had his parachute harness on, but not his chute. He snapped it on, and bailed out.

"My co-pilot wouldn't leave until I promised to follow him," said George Oxrider, "so I told him to go ahead, I'd follow him, When they were all gone, I shut off the alarm bell-it made a hell of a racket-and slipped the plane through the hole in the overcast. My one engine was purring beautifully-it never did get hot. After two or three circles, I levelled off to land on a rugby field, coming in pretty fast. And then out of nowhere, a bunch of kids appeared in the middle of the field. Down at one end, there was a wooden flagpole, a hedge, and beyond that, another field with several roller coaster bumps in it, and a tree lined wall at it's end. I gunned the motor for what little it would take, cracked off the end of the flagpole, skipped the hedge, and set the plane down fast. It was an alfalfa field. I landed on one rise, went up and down to the next, up and over that one, and then I shoved the stick forward, so that the wheels would plow into the ground. They did, too. When she stopped, her wheels were in the soft ground up to the hubs, and her nose came to rest between two trees, only a few feet from the stone wall."

As George Oxrider climbed from his plane, he was greeted by a large number of people who had come streaming out from the nearby buildings. It didn't take him long to figure out that they were hospital patients, and that he had set his plane down in the grounds of one of England's biggest mental institutions.

Werewolf was hemmed in by trees, hedges and walls, and the road was too narrow for the plane to be removed that way. Thus it was initially thought that she would have to be dismantled in order to get her out of the cabbage patch.

Then, in came the American Engineers, under the command of Lt. Col. Charles R. Broshus, with: "If the Air Corps can get it in here, the Engineers can get it out." And so, twenty men, equipped with a bulldozer, grader, caterpillar and dump trucks got down to work.

They felled oak trees, removed 120 feet of wall, and a hedgerow, making a 2,250 feet runway strip, adding a further 1,000 feet, for reasons of safety, by clearing and compacting fields at the end of the "runway". Fourteen days after landing, Werewolf revved up with three new engines installed by a Mobile Repair Unit and went gracefully on her way, kicking up the biggest dust storm ever seen in the area, and passing right over the head of one farmer who had lost a number of oak trees.

Werewolf would not return to the 303rd Bomb Group again. First, it was flown to Honington, then on April 22, 1943, it was assigned to the 401st Squadron of the 91st Bomb Group, but not for long. On June 11, Werewolf went to the US 3rd Base Air Depot at Langford Lodge, then on June 14 to Little Stoughton (8th Group RAF Bomber) and finally to 1st Combat Crew Replacement.

Exactly 50 years after he had parachuted onto Dartmoor, Werewolf's radio operator Everett Dasher returned to the exact spot on which he had landed. It was a typical English winter's day. Cold, raining and with a strong wind blowing. Everett was taken onto Dartmoor in a restored American World War II jeep, in company with Monica Alford, then a teenager, who had rescued him on January 23, 1943, and with whom he had kept in contact since that day.

Afterwards, Everett and his wife, Helen, visited the place where George Oxrider had landed in Werewolf, and then on to the Mayor of Dawlish's Parlour and an official civic welcome. He met many of the people who had witnessed the landing of the Flying Fortress.

[Researched by Harry D. Gobrecht, 303rdBGA Historian Emeritus]