|

"Outfield Fly" Buzzing the 1943 World Series |

Personnel

Mission Reports

by Hap Rocketto

first published in Air & Space Magazine August/September 1993

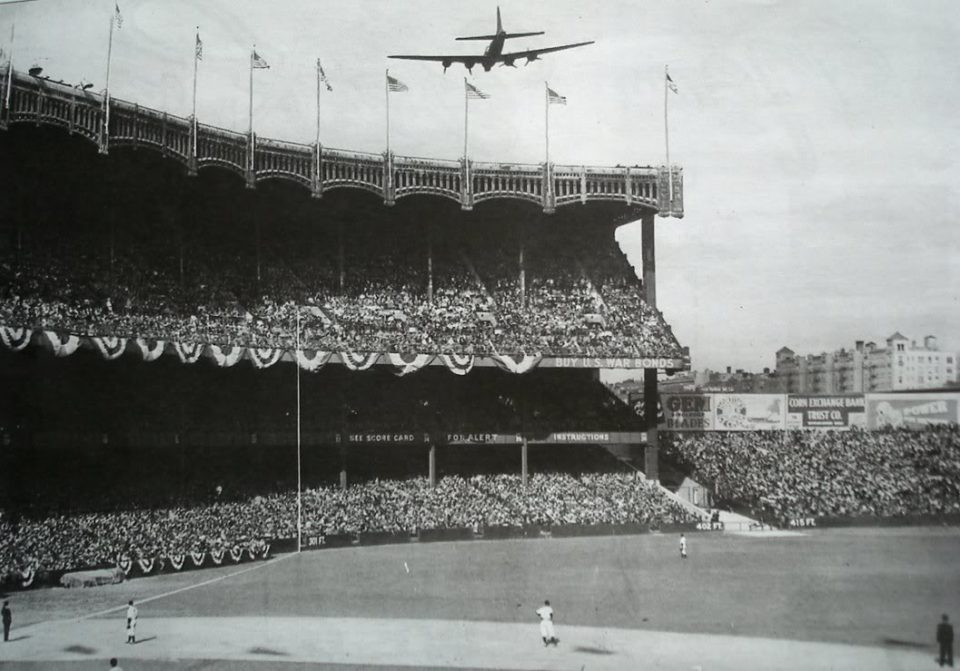

AP Photo, published in the NY Times, October 6, 1943

The 1943 World Series had all the hallmarks of a classic. In a rematch of the previous year's antagonists, the St. Louis Cardinals would attempt to repeat their resounding win over the New York Yankees. The 1942 Cardinals had not been given much of a chance against the New York powerhouse, but with the batting of rookie Stan Musial and the pitching of Johnny Beazley they defeated a team that had won six league championships in seven years.

But the nation's war effort was gobbling up manpower at a prodigious rate. No one knew who might be playing ball in 1944, or if there would even be a 1944 season. It looked as if this might be the last great series for the duration of the war, which is why the first game drew over 68,000 fans to Yankee Stadium.

As the teams took batting practice and the pitchers warmed up, four Army Air Forces B-17 bombers were droning toward New York City on their way to combat bases in England. At the navigator's station of Thru Helen Highwater [42-39785], sat my uncle, Second Lieutenant Harold Rocketto of Brooklyn. Second Lieutenant Jack Watson was the pilot; the other bombers were piloted by Second Lieutenants Robert Sheets, Elmer Young, and Joseph Wheeler.

As Rocketto, a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, scanned the landscape trying to pick out boyhood haunts in the Bensonhurst section, the idle chatter on the intercom turned to the World Series. No one is sure what sparked the next move. Perhaps it was Rocketto's desire to seek revenge against the Yankees for their 1941 victory over the Dodgers. Then again, perhaps it was just the high spirits of young men facing a dangerous future. Whatever the reason, the fans at Yankee Stadium were about to be treated to an impromptu demonstration of the nation's bomber force.

As the aircraft crossed the Hudson River, the pilots headed for the Bronx and put the formation into a shallow dive. Picking up speed, the bombers thundered over Yankee Stadium in a low pass from home plate to center field. After they climbed out the B-17s wheeled about and circled the field while Watson returned for an encore. He cleared the upper-deck flagpoles by a mere 25 feet, prompting the Associated Press to later report that "an Army bomber roared over Yankee Stadium so low that Slats Marion could have fielded it." Watson then rejoined the formation and headed east.

"We knew we were heading for a combat zone and dropping in on the World Series seemed like a good idea at the time," Wheeler told a reporter months later. "The announcers must have thought it was part of the show because after we went over the first time we could hear them on the plane radio talking about the big Air Force review. We figured they were enjoying it so we turned around and came over a second time. We thought nothing about it until later when we found we had caused a sensation."

New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, a World War I Army pilot, was watching as the bombers swooped overhead. La Guardia initially appreciated the panache of the young men, but admiration quickly gave way to his greater duty as mayor. Outraged, he burned up the phone lines to the Army Air Forces brass. "That pilot should be properly disciplined, endangering the lives of the citizenry of New York in that manner," he fumed.

When they landed at Presque Isle Airfield in Maine, Watson and the three other pilots were confined to quarters while court martial proceedings were undertaken. They were released a few days later when the Army realized it was foolish to keep four badly needed aircraft and crews out of combat because of a youthful indiscretion. "Besides," a general told Watson, "you and your crew will probably be killed anyway."

Five days after the buzzing brouhaha the four aircraft continued their journey to England, each pilot's military record heavier by a letter of reprimand and his wallet lighter by a $75 fine - no small sum to a second lieutenant back then.

Because of wartime news restrictions so tight that sports announcers were forbidden to comment on the weather lest the enemy pick up valuable intelligence, the buzzing incident went almost entirely unreported. The names of the crews were unknown to all but the authorities until three months later.

January 11, 1944, was one of the costliest days of air combat in history. Some 60 U.S. bombers were destroyed and more than 600 airmen were killed, wounded, or reported missing. On that terrible day. Watson, flying with the 303rd Bomb Group, single-handedly returned his badly shot-up and burning bomber to England. In a radio interview he brought up the stadium incident by voicing hope that the mayor of New York was not still sore at him. After hearing the interview, LaGuardia sent Watson a message: "All is forgiven. Congratulations. I hope you never run out of altitude. Happy landings. We'll be seeing you soon."

"Thank you, Mr. Mayor, and it can't be

too soon for me." Watson replied, then

added, "We'd sort of like to go back

together some day and drop in on the

Rose Bowl game."