|

303rd BG Original Crew 359th Witt Crew Orville S. Witt, Pilot |

Personnel

Mission Reports

ORVILLE S. WITT CREW - 359th BS

B-17F #41-24566 Zombie (359BS) BN-W

(Lt Witt assigned 359BS: 23 June 1942 - photo: 10 Oct 1942)

Departed Kellogg Field, Battle Creek, MI on 03 Oct 1942,

arrived Molesworth England on 25 Oct 1942

(Back L-R)

1Lt Orville S. Witt (P)(KIA)(1),

2Lt George C. Woodman (CP)(KIS)(2),

2Lt Donald H. Brightbill (N)(KIA)(3),

2Lt Wilmer E. Dyar (B)(KIA)(3)

(Front L-R)

S/Sgt Lyle C. Woods (E)(KIA)(3),

Cpl Edmund R. Thornton (R)(4),

S/Sgt Warner E. Renner (BTG)(KIA)(3),

Sgt Thomas F. "Dude" Bachom (Assistant Radio)(KIA)(3),

S/Sgt Lawrence W. Thomas (TG)(KIA)(3)

(** Woods and Thomas may be reversed)

Note:

1Lt Richard E. VanHoldt, Weather Officer, was a passenger on the overseas flight.

There were no waist gunners on the overseas flight.

Combat Crewmen and missions flown:

- 1Lt Orville C. Witt (P)(KIA) - Flew on 2 missions (#2 - 11/18/42 and #7 -

12/20/42)

- 2Lt George C. Woodman (CP)(KIS) - No missions with the 1Lt Witt Crew.

Two missions (#17, 21) with other Pilots. Substitute CoPilots

on Lt Witt missions: #2 -1Lt Herbert E. Kalhoefer; #7 - 2Lt Francis

M. McMurty, Jr. (KIA). Woodman died in the "Line Of Duty" as the result of a plane crash in Northern Ireland during the war.

- 2Lt Donald H. Brightbill (N)(KIA), 2Lt Wilmer E. Dyar (B)(KIA),

T/Sgt Lyle C. Woods (E)(KIA), T/Sgt Thomas F. Bachom (R)(KIA),

S/Sgt Harold A. Kinsey (WG)(KIA), Cpl Bernard W. Millett (WG)(KIA),

S/Sgt Warner E. Renner (BTG)(KIA), S/Sgt Lawrence W. Thomas (TG)(KIA) -Two missions with 1Lt Witt

(#2, 7); Two missions with Major Eugene A. Romig

(#3, 7). All KIA on mission #7

- Sgt Edmund R. Thornton (R)(POW) - No missions with the 1Lt Witt Crew. Flew on 11 missions with other 4 different Pilots : (17)(A), 18, 19, 20, 21(A), 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 - (A) Aborted missions). POW on mission #28, 04 April 1943 to Paris, France, 1Lt Ercil F. Eyster (Pilot), in B-17F #41-24609, Holy Mackerel (359BS) BN-Q [MACR 15069], Shot down by Enemy fighters (6 KIA, 4 POW).

Mission #7, 20 December 1942, in B-17F #41-24566 Zombie (359BS) BN-W. Shot down by enemy fighters and ditched in the English Channel [MACR 15708) - All ten crewmen were Killed in Action.

by Barry Udoff

|

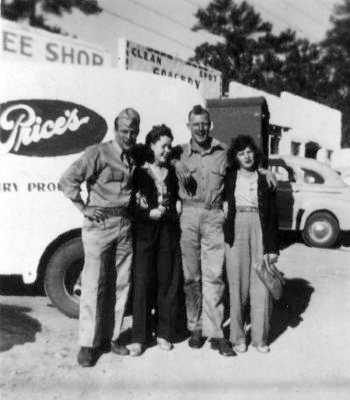

Dude and Jack grew up in Los Angeles, the sons of Esta and Tom Bachom. It took a sharp eye to identify the boys as brothers. What similarities they had were buried beneath their differences. Both were tall and good-looking but Jack was sketched out all in circles, as if with a compass; Dude, in vertical lines drafted with a T-square. Jack's tight grin seemed to be suppressing a laugh. Dude lacked this restraint. When he laughed, seismic rings rose up in coffee cups. The brothers' resemblance was all but erased by Dude's meandering waves of red hair. Jack and Dude had graduated high school the year before Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. Jack enlisted in the Navy, Dude in the Army Air Corps. within weeks of America's declaration of war.

Their willingness to fight was a trait passed down from their mother's family. Esta's father, John Buckhold, had volunteered for an Ohio Regiment soon after the Civil War began. His infantry fought brutal battles along the western front, including a savage clash in Franklin, Tennessee. When the regiment disbanded in 1865, a third of the original volunteers had been killed or wounded.

John survived and returned to his Ohio farm. He married and became the father of two daughters, Mimi and Esta. To have daughters was a merciful turn of fate for a man who knew the sacrifices that sons make in war. And the next war was already germinating; a war that would end them all, an illusion crushed 20 years later. In this war, John's daughter was not granted the mercy that he had received. With two sons in military service, Esta was a "Blue Star" mother, entitled to drape two flags from her porch. The blue stars were replaced with gold when a family lost a member.

Dude's niece, Sandi, has her uncle's red hair. She is now an attractive, youthful woman of 63, living in New York as an author and filmmaker. She is also the curator of the family museum kept on an antique mahogany library table. On display are framed tintypes of her 19th ancestors. Among them is an image of her great grandfather, John Buckhold, wearing his regimental uniform.

|

The photos move us forward, a family of four in a Model-T driving across the pages. Time collapses smoothly, slowing down to record Esta's marriage to Thomas Bachom. Here is where the photos of her sister, Mimi disappear; hopefully migrated into an album that has become another family's heirloom.

Each of the last two pages of the album holds a single snapshot. On the left page, Jack wearing his Navy uniform strikes a casual pose standing between his parents, who in contrast, are as stiff and upright as stalks of corn. This is Jack's last home leave before he sails. He can't hide his excitement. His father appears confused, unable to gather his emotions into a single expression. Esta, from under a stern, flat glare conveys the sorrow and fear she feels for her first-born son. The photo on the right seems a mirror image of the opposing page. But there is a difference. In this photo, it's Dude who wears a uniform and stands between his parents. This is Dude's last home leave before crossing the Atlantic to join the air war against Germany.

Dude arrived at Briggs Field in August of 1942 to begin advanced training as a member of the 303 Bomber Group. Briggs Field is located near El Paso on the flat Texas border that seems to hold New Mexico on a shelf. For 60 days, he trained, learning to be a B-17 radio operator. It was a position that included the mastery of complicated aeronautic radio equipment, competency in air-to-ground photography and, when necessary, the ability to fire the 50-Caliber machine gun mounted in the top turret aft of the cramped radio room.

|

The tail gunner's position on a B-17 offers a spectacular view. It's a greenhouse with a gun, a perch to observe the awesome geometric formation of 100 flying battleships sailing through a vast sea of sky. But the vista changes as the bombers approach their target. The sky begins to explode in black blooms of flak that can rattle a ship to its rivets and threaten to toss it from the air. Some airmen were more fearful of flak than the German fighters. Luftwaffe attacks could be fought off with machine guns. Flak could not be shot down.

When the flak stopped, the enemy fighters took up the battle. They gathered in clusters ahead and behind the bombers and began their charges, aiming for front or tail shots, ripping the sky with their 20 MM machine guns at 15 rounds per second. Frontal attacks could shatter the flight deck killing both pilots, sending the bomber down in an uncontrolled spin. A few parachutes might pop from the hatches or the bomb bay doors, but not often. Bailing out of a bomber in a tight spin must be like trying to crawl out of a rolling barrel.

The Army Air Force, like any large corporation, kept track of its inventory with paperwork. After every mission, ground crews tallied the number of rounds each gun had fired and measured the gallons of fuel burned on the flight. Pilots were debriefed and required to submit written accounts of weather conditions, the location of enemy fighter attacks, bomb damage assessments and the all-important scorecard of "EA" (Enemy Aircraft) shot down. In the chaos of air battle, it was difficult to know which guns had sent a German fighter down in smoke. Sometimes more than one gunner took credit for the same "Kill." The solution was to use fractions that gave multiple gunners a portion of the score. The most chilling eyewitness reports were those that described the loss of one of their own.

On December 20, 1942, Dude and his crewmates were part of a mission that had bombed a German airfield west of Paris. They had been fighting a running battle with German fighters all along their return route. The B-17 they had christened "Zombie", was flying over the English Channel heading for its south London base when it was hit.

There are at least three versions of the "Zombie's" last minutes in the air. One pilot wrote, "B-17 went down apparently under reasonable control in tight spiral. Part of # 2 motor shot away, # 4 motor on fire." From a different witness, "…B-17 circling near coast of France-2 engines on fire…being attacked by several EA." Another pilot"…saw this ship go down-5 chutes seen to open." This was a wishful report. None of the crew escaped the crash. And there is the account that doesn't appear in the official records. It was recorded by a B-17 radioman flying behind the "Zombie" when it went down. In a letter to Sandi written 60 years after Dude was lost, he writes, "I knew your Uncle…He was the squad comedian, he kept everybody laughing...When the "Zombie" was hit, I followed it down to the water. When it ditched, I think the top turret gunner was still firing." The flier who had taken the picture of Dude in his Mohawk wrote the letter.

There are at least three versions of the "Zombie's" last minutes in the air. One pilot wrote, "B-17 went down apparently under reasonable control in tight spiral. Part of # 2 motor shot away, # 4 motor on fire." From a different witness, "…B-17 circling near coast of France-2 engines on fire…being attacked by several EA." Another pilot"…saw this ship go down-5 chutes seen to open." This was a wishful report. None of the crew escaped the crash. And there is the account that doesn't appear in the official records. It was recorded by a B-17 radioman flying behind the "Zombie" when it went down. In a letter to Sandi written 60 years after Dude was lost, he writes, "I knew your Uncle…He was the squad comedian, he kept everybody laughing...When the "Zombie" was hit, I followed it down to the water. When it ditched, I think the top turret gunner was still firing." The flier who had taken the picture of Dude in his Mohawk wrote the letter.

On Christmas day, 1942, a War Department telegram arrived and informed Esta that her son was "Missing in Action", a term that conveyed a hope that the words "Killed in Action" would have obliterated. She was still clinging to this distinction when Sandi was born on October 14, 1944, two years after Dude's death. On the day of Sandi's birth, Esta visited the Bulocks Department store on Wilshire Blvd. After choosing a silver rattle, she gave instructions for it to be engraved with the baby's name, date of birth and the name of the man who would give it to her. It was a gift from an uncle she never had; given to a niece he would never know.

A mother can give her child life only once. And so to deny the death of her son was the only means she had to protect him from harm. The intractable terms of her refusal were engraved in graceful script on a silver rattle. It didn't bring Dude back to life, but it kept him in memory and brought him back from the missing.

Sandi keeps the rattle next to a framed photo of her "Uncle Dude" in his Mohawk hair cut. The rattle is a miniature version of a judge’s gavel with a slender handle tapering down to a barrelhead. The silver reveals so few scratches it's evident Dude’s gift spent little time clutched in his niece’s hands. You pick it up and read the engraving as holy writ. You shake it. You find it impossible to distinguish the faint chimes from the echoes they leave behind.

[Researched by Historian Harry D. Gobrecht]