|

The Evasion of Alfred Buinicky |

Personnel

Mission Reports

by Abbe Robert Bauvais

Article and Information provided by Michael M. LeBlanc - Translated by Jean and Margaret Heesen-Schoch

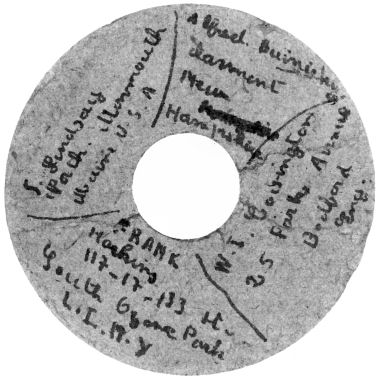

Abbe Bauvais was a Comete Line member in the French Resistance. He was eventually arrested in Paris on 01 March 1944 and survived the concentration camp, though his mother and sister did not. The article, written in French, contains some errors. S/Sgt Alfred R. Buinicky was actually from New Hampshire rather than New York. On the insulator ring shown below, you can read his name as "Alfred Buinicky, Claremont, New Hampshire." Though it seems he did evade capture for a time, eventually he was arrested and spent the rest of the war as a Prisoner of War.

S/Sgt Alfred R. Buinicky was the Ball Turret gunner on the 358th BS William J. Monahan Crew. The crew went down on 31 August 43 mission #65 to Amiens/Gilsy, France in B-17F #42-29635 Augerhead (358BS) VK-M. The B-17 lagged behind formation, pulled out of the formation heading for the coast and seeking cloud cover from attacking enemy fighters. It was last seen going down over Abbeyville, under control, with two enemy fighters attacking. More information on this incident is on the Monahan Crew page.

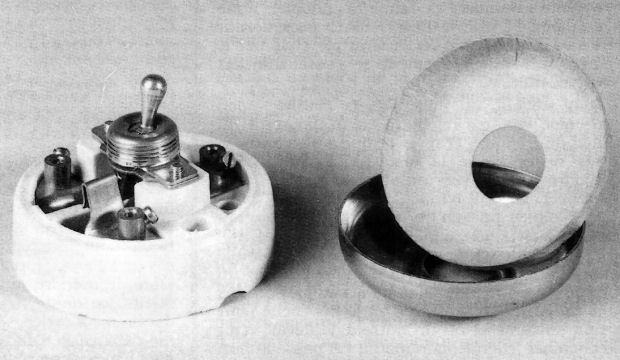

The reader may be surprised by the reproduction of an electric switch and of the ring inside. Here’s the explanation:

During the time of the occupation, anyone implicated in a Resistance organization or in any evasion efforts, like the Comete, risked imprisonment or deportation; that’s what happened to Father Beauvais.

However, he multiplied the precautions. Obviously he was worried not only to be discovered by the Gestapo, but he also wanted to protect those whom he had helped and hid out: this was true of the aviators who had been shot down under occupied territory.

The reader may be surprised by the reproduction of an electric switch and of the ring inside. Here’s the explanation:

During the time of the occupation, anyone implicated in a Resistance organization or in any evasion efforts, like the Comete, risked imprisonment or deportation; that’s what happened to Father Beauvais.

However, he multiplied the precautions. Obviously he was worried not only to be discovered by the Gestapo, but he also wanted to protect those whom he had helped and hid out: this was true of the aviators who had been shot down under occupied territory.

Many were those who were taken charge of and transported by the evasion group, the Comete.

Another problem was to try and keep a record of them in order to assure some kind of a link with their unit. He needed to do his utmost to find a hiding place that was as secure as possible. An electric switch, at least those that existed in large numbers for about fifty years, included a screw top lid whose internal side was covered with an insulation material in the form of a ring: it was on this, invisible even with the lid unscrewed, that Father Beauvais wrote the names of the four members of a B-17 crew whom he had taken charge of from Paris at the time of their evasion towards the Pyrenees and into Spain. Harkins, one among the four, is the author of the adventures we are publishing.

From the Skies of Dunkirk to Stains

The American B-17 “Flying Fortress” hit by flak over Dunkirk had broken in two. The five men in the tail of the plane were not able to parachute out and it crashed in the countryside.

The right waist gunner, Alfred, succeeded in getting out with five other crewmembers. The parachute drop seemed long, really long. Let’s hope the heavy guns don’t shoot! Of course, that’s against the Geneva Convention. It’s a “war crime” to shoot at an airplane crew in distress. That’s the law, but for the Nazis, one death is the same as another at their hands. I saw with my own eyes the crew of a B-17 “Flying Fortress” parachuting not far from Paris. Heavy machine guns fired upon the ten men whilst they fell 5000 meters. Not one was taken prisoner, all of them were shot full of holes. A succession of war crimes, one after another! The assassin was seen by thousands of Parisians. At Dunkirk all went well.

While the B17 “Flying Fortress” crashed with the five men captive in the tail, Alfred had landed in the countryside: a good landing, no wounds.

Hastily, he folded his parachute, fled as far as possible from his landing position, hid the parachute in the brush, and planned his next move.

His survival pack contained a lovely little silk map of France. This map permitted him to get his bearings and to foresee his escape route towards the south. But south, Paris first.

His rescue kit, which was about the size of two big boxes of matches, contained pills for keeping him awake and for fighting off fatigue, some pills to purify water, a small knife, a fishing line and an adorable tiny compass. As for food! My dear Alfred, sort it out for yourself! fruits, apples and maybe a piece of bread or some soup. If you are lucky enough to find a brave and hospitable farm, that is, because the discovery of an aviator in a home, that is arrest, prison, torture and one day deportation of all family members. The Gestapo is everywhere; the militia of Darnard is omnipresent.

Fear fabricates informers, not to mention “collaborators.” In spite of it all, the horror of the “Aryan race,” the love of liberty and the respect of human dignity stay in the guts of the people, despite the brainwashing. “Marechal here we are!” (This was a very famous song in those days, referring to Marechal Petain) So, Alfred walks, not on the main road that follows the railroad line, Dunkirk/Paris, but along the border where he is able to throw himself into a ditch at the slightest sound of a German convoy or an isolated car.

How much time will it take for this long march? Perhaps four or five nights.

Arriving not far from Paris, in Pierrefitte, Alfred heads away from following the tracks and enters into a large village. He is in Stains. During this time it is a village with many farmers who sold goods at the markets. The church is in the center of the small town. Maybe Alfred should enter Our Lady of Assumption in Stains? Providence does not present Himself. Too bad, because had he forced the door open a bit he would have found a wonderful little priest who would have sheltered and rescued him. I know this area perfectly, as I celebrated my first Mass there on June 30, 1936.

Alfred continues.

Two hundred meters further on is the City Hall. No interest in this City Hall – communist in 1936: now in 1943, pampered, therefore, collaborators.

Alfred continues.

Two hundred meters further on is the City Hall. No interest in this City Hall – communist in 1936: now in 1943, pampered, therefore, collaborators.

But across from the City Hall is a beautiful, large residence surrounded by trees. This is the religious community of St. Vincent De Paul. Women with the large white headdresses (nuns) running a home for distinguished older women.

Clearly this was hope and joy for Alfred: he just caught sight of one of the white headdresses! Alfred discreetly approached the religious woman. She knew that far, far away towards the north, above Dunkirk, an allied B-17 “flying fortress” had been shot down. The man in front of her is an escaped American aviator. All the sudden her face lights up, she motions to him and Alfred follows her.

Several minutes later Alfred is shown to a small room and converses with an older lady who speaks English. This part is won. Alfred is exhausted and temporarily saved.

Is one able to imagine today, in France, three women, the Mother Superior, the young novice with her white headdress, and the older lady, why they risked their lives?

Picked out and arrested by the Gestapo, they certainly would have ended their lives in Ravensbruck or shot by a firing squad. It was around this same time that a female resistance fighter was decapitated with a hatchet, on June 3rd, 1943, wasn't it?

Alfred regains his strength. What cleanliness, what comfort, what good food, what a great bed. But “it’s a long way” …..to Gibraltar and England!

From Stains to St. Thomas Aquinas

For the French people of today, who did not experience the occupation under the Nazis, it is extremely easy to go around by bus, metro or train. It was another thing back in 1942, 1943, and 1944, especially if you were accompanied by a “package” that spoke not a word of French. No one escaped verification of one’s identity by the police, who were submissive to their superiors, and even “collaborators.” No one could hide from the dangers of the militia or from an unexpected search. What does one do if responsible for a human life? Count on Providence or play the game of “all or nothing.”

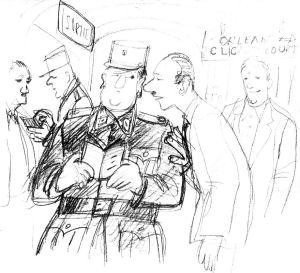

Here’s an example of this unthinkable reality. My friend, Robert Ayle, who was shot at Mont Valerien with Frederic De Jongh and Aimable Fouquerol, was stopped one day in the corridor of the metro. An aviator was walking behind him. All the sudden a plainclothes civil patrolman was checking identity papers: the American, taken in for questioning would not have gotten away. Robert concurs with the official, “Officer” he says to the policeman- “let him go, he’s an American aviator.” Taken aback the cop replies, “who’s going to prove it?” Robert negotiates for several minutes giving him material proof. “Let him go,” says the policeman, “I checked him” he yelled to his colleague a little further on – “it’s O.K.”

Here’s an example of this unthinkable reality. My friend, Robert Ayle, who was shot at Mont Valerien with Frederic De Jongh and Aimable Fouquerol, was stopped one day in the corridor of the metro. An aviator was walking behind him. All the sudden a plainclothes civil patrolman was checking identity papers: the American, taken in for questioning would not have gotten away. Robert concurs with the official, “Officer” he says to the policeman- “let him go, he’s an American aviator.” Taken aback the cop replies, “who’s going to prove it?” Robert negotiates for several minutes giving him material proof. “Let him go,” says the policeman, “I checked him” he yelled to his colleague a little further on – “it’s O.K.”

Providence had intervened. If it had happened another way, what would Robert have done? – I would have gone all the way – I would have killed the two police officers…and he would have shown me the gun in his coat pocket that he had taken from the German soldier in the metro.

Everything worked out for Alfred and the young priest “little Robert,” who guided him from Stains to 1 rue de Montalembert – 5th floor on the left, the rectory of the priests of St. Thomas Aquinas. Not one of these priests noticed the secret activity that essentially consisted of bringing aid to people in danger and in rescuing aviators, who maybe without consciously realizing it, fought, like us, like Robert Ayle, like Frederic, like Alice and many others, against the most frightening ideology that has surfaced and possessed power, a destructive ideology to all those who are not considered of the Aryan race.

For Alfred, his life passed peaceably with a few escapades guided by my sister, Renee, to 17 Boulevard Raspail, home of the parents of one of my liaison agents, Louis Rousseau. Between two sessions of the National Council of the Resistance, presided over by the successor of Jean Moulin, Georges Bidault, who had been chosen by Charles de Gaulle, Madame Rousseau offered her hospitality for a brief time to one or two wounded aviators who had just visited a professor from Laennec. The stay in Paris is over!

The truth comes out, “Franco” the smuggler. The route went south through the Pyrenees. Alfred left with five other aviators. After a perilous voyage he arrives in Gibraltar, then London. Alfred resumes combat but in a terrible sector: the Battle of the Pacific.

One day he finds himself back in New York. Could it be that for several years he has been driving a big bus? The people that he transports, even the ones from the Bronx or Harlem are much more likeable than the S.S. from Europe or those “well brought up” Japanese, the ones who were so cruel in the name of their Emperor Hirohito!

So long Alfred from New York

24 November 1943

There were four airmen traveling south of Bayonne on bicycles, having stayed in a house about 5 miles south of Bayonne. Guide 1 was followed 100 yards behind by F/Sgt Grout and an American. Then there was Guide 2 and a hundred yard gap to Buinicky and Bruce.

The signal, if there was danger in front, was for one of the guides to wave his beret, and the evaders would have to get off their bikes and scatter. At approximately 1700 hours on 24 November 1943, two Germans on a motor bike and sidecar passed by Bruce and Buinicky, but seemed to take no notice of them. However, at a bend in the road they saw the Germans turning back, so the two turned their bikes around and cycled back up the road they had come, as there was 12 foot barbed wire all the way along the section of the road they were on.

Before they could get clear of the barbed wire the Germans were on to them and demanded their papers. Bruce had memorized the details of his papers and spoke some French, which measured against the poor French of the German. Bruce felt that he had done OK, but it all fell apart when they questioned Buinicky, as he could speak no French. They were arrested and taken to the Frontier Post. Grout and the American plus the two Guides got away.