|

360th Smith Crew Samuel W. Smith, Pilot |

Personnel

Mission Reports

SAMUEL W. SMITH CREW - 360th BS

(crew assigned 360BS: 06 Feb 1945 - photo: 02 Apr 1945)

(Back L-R) 1Lt Samuel W. Smith (P), 2Lt Arthur S.C. Shanafelt, Jr. (CP),

F/O Russell A. Knudson (N), S/Sgt Earl K. Lawson (WG)

(Front L-R)

S/Sgt Walter A. Geyer (TOG - holding "Tailspin"),

T/Sgt Robert A. Bridgman (R),

S/Sgt Jens C. Jensen (TG),

Sgt Michael J. Kucab (BTG),

T/Sgt Thomas E. Zenick (E)

[photo from the 303rdBGA Archives - identification by Samuel W. Smith]

Crew Recalls Wartime Experiences

by Terry Collier

©copyright Fredericksburg Standard Radio Post, April 29, 1992, used by permission

transcribed by Shari Shanafelt

JUST KIDS--- 06 Feb 1945 - Pictured [above] with a canine friend in front of their B-17 during a break from flying missions over Germany and France in World War II are members of the "Jackie" crew. All in the crew were either 19 or 20 years old except for one who was 25......

In their 24 missions over Germany and France, the B-17 bomber crew of Fredericksburg resident Samuel W. Smith accomplished a lot for the Allied cause in helping end World War II. But for two American prisoners of war, all the bombs the crew of the "Jackie" dropped in 1944-45 were nothing compared to what Smith's buddies did as the war in Europe was winding down. Recently liberated from a German POW camp somewhere in Europe, the two American captains had been transported to England and then had been given orders to return to the U.S. by ship on the next available transport. But before that slow trip could come about, Smith's bomber crew came into their lives.

"On the morning that we were to fly back home from Scotland with a new plane to prepare for the invasion of Japan, we met these two fellows huddled under our plane," remembered Smith one day recently as he sat around a table here with his bomber crew mates, some of whom had not seen each other in 47 years since the end of the war.

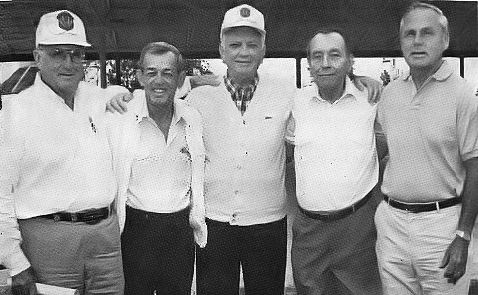

TOGETHER AGAIN-- Five of the original nine members of the "Jackie" B-17 crew that flew 24 missions over Germany and France during World War II gathered here recently for a reunion at the home of Fredericksburg resident and crew commander Sam Smith. From left are Smith; Arthur Shanafelt of Jacksboro, Texas; Tom Zenick of Morristown, NJ; Robert Bridgman of Kansas City, MO, and Earl Larson of Lawton, Michigan. ---Standard-Radio Post Photo |

"After their captivity, these two officers were still skin and bone, and the only possessions they had in the world were in a little bag of personal belongings that they each carried with them," he recalled. They spent the night in the plane and were waiting for us because they had heard somehow that we were going back to the States and wanted to ride with us."

Smith said he and co-pilot Arthur Shanafelt of Jacksboro, Texas, who was among the five men who recently reunited at Smith's Gillespie County farm, had misgivings about an unauthorized ride for the two ex-POWs. After all, though they had not experienced the anxieties and problems of imprisonment, still Smith's crew of nine had just come through some pretty tough times of their own.

After four months training as a crew in the U.S., the men of the "Jackie" -- the same type of bomber featured in the recent movie Memphis Belle -- flew 24 missions over Germany and two over France from February through April of 1945.

"We were really just a bunch of kids," Smith remembered, noting that with the exception of tail-gunner Jens Jensen of Montana, who was 25, everyone else on the four-engine "Flying Fortress" was either 19 or 20 years old. Other crew members included Robert Bridgman, radio operator from Missouri; Tom Zenick, engineer from New Jersey; Earl Lawson, waist gunner from Michigan; Mike Kucab, ball turret gunner from New Jersey; Russell Knudson, navigator from California, and Walt Geyer, nose gunner from North Dakota. Smith himself was a native of Goldthwaite and after the war became a chemical engineer for the Norton Company before retiring here in 1989 to a farm he had purchased 12 years ago.

Their missions during those three months took them over some of Germany's most important manufacturing centers. They and other members of the 360th Squadron in the 303rd Bomber Group ("Hell's Angels") of the 41st Combat Wing flew 364 missions over Europe during WWII and dropped more tonnage than any other group in the 8th Air Force. According to a book (Reflections of a Bomber Crew) that Smith has put together about his buddies and their role in the war, the "Jackie" under his command dropped bombs on a variety of targets, including railroad yards, shipping ports, oil refineries and factories located at or near such familiar places as Berlin, Leipzig, Bremen, Essen, Munich and Hamburg.

Frequently, their plane sustained damage from fighter attacks and flak fired by defensive positions in Europe. "But we were extremely fortunate that we never had a man injured," Smith said, adding that their plane was damaged many times and was not flyable after landing back in England. His crew felt fortunate also to have had a phenomenal ground crew at their base 70 miles north of London in the Midlands at Molesworth Station.

"Our ground crew chief and his two helpers would stay up all night, if necessary, to patch up the plane after we'd come in with holes all over the place," Smith recalled, "and we never took off with any malfunctions after they were finished." As for the crew itself, Smith said that a close bond developed among the nine men.

"When people start shooting at you, you learn to depend on each other," he said. "It may sound strange, but you become more attached to these guys as a crew at that point in your life then you do to your own family."

Shanafelt, who with Bridgman, Zenick and Lawson recently reunited here with Smith agreed, adding, "It is a feeling that you almost can't describe, but when you rely on people around you for your life, that carries on even today."

Smith said that, because the pilot and co-pilot couldn't see everything around their aircraft at one time, they learned to depend on tips from their crew. "Our gunners would radio up to us that there were fighters coming up or that we should adjust our course to avoid some flak," Smith remembered. "Frankly, if it wasn't for everyone helping out, we wouldn't be here today."

So on that morning in Scotland, after just safely coming through those 24 missions over Germany and France, Smith and Shanafelt were understandably a little uneasy about offering an unauthorized ride to a couple of American ex-POWs.

"But there was something about those two guys," Smith remembered. "To have survived the fighting, then being taken prisoners before making it back to England and finally finding us way up there in the central part of the country told us that these two were most resourceful fellows."

"How could we have said 'no' to them," he asked, adding that, when the crew said they would secret the two stowaways back to the U.S. in their plane, "their joy was so great that they jumped up and down and danced around our plane."

On the long flight home, the bomber made stops in Iceland and Labrador. "We would sneak food out to them where they were hiding in our plane," Smith said.

"During the stopover at Reykjavik (Iceland), we and other bomber crews were gathered in a briefing room and were advised by a colonel that we weren't supposed to have any undeclared personnel on our planes and that, if we did, we had better declare them at once," Smith remembered.

"Shawnie (Shanafelt) and I were sitting right in front of him in the third row and figured he must know about our cargo and was testing us," Smith said. "But we didn't say a word and got off without anything coming of it."

When the bomber formation eventually landed in Connecticut, Smith said the last he and his buddies saw of the two former POWs was them running from the plane and across the grain field. "We never saw or heard from them again," said Smith who said the only other thing he remembered about the two men is that they had orders to report to Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio where they were to be checked out for any medical problems that might have resulted from their imprisonment by the Germans.

"We didn't ask them their names -- we really didn't want to know in case we were asked later -- and they didn't want to know ours either," Smith said. "But I've often wondered what ever happened to them."