|

359th Bailey Crew Jack W. Bailey, Pilot |

Personnel

Mission Reports

-S.jpg)

JACK W. BAILEY CREW - 359th BS

B-17G #42-97944 Daddy's Delight (359BS) BN-I

(crew assigned 359BS: 01 Dec 1944 - photo: 19 Jan 1945)

(Back L-R) 2Lt Jack W. Bailey (P-Rtd), 2Lt Merwin G. Hall (CP-Rtd),

2Lt Glen R. "Swede" Swenson (N *), 2Lt David E. Johnson (B *)

(Front L-R)

S/Sgt Elwyn J. Darden (R-POW),

Sgt Carl A. Muller (E-POW),

S/Sgt William E. McGuire (WG/Tog-POW *),

Sgt Merle W. Eckert (TG-POW),

Sgt Donald F. Geng (BT-POW)

- 2Lt William H. Fisher (N-POW), from 2Lt Fred E. Call Crew for Lt Glen R. Swenson (N) who became a Lead Crew Navigator.

- S/Sgt W.D. McGuire (Tog-POW) (Regular crewman Waist Gunner) for 2Lt David E. Johnson (B) who became a lead crew Bombardier

- S/Sgt Edward L. Bartowiski (WG) for S/Sgt W.D. McGuire (WG)

While CoPilot 2Lt Merwin G. Hall was checking the Fortress to make certain that all crewmen were out, four P-51s showed up and drove off the enemy aircraft. Lt's Bailey and Hall then decided to attempt to bring their damaged B-17 back to friendly territory. They bailed out near St.Trond, Belgium and returned to Molesworth. The pilotless Fortress made a wheels up belly landing near the hamlet Boekholt of the city of Straelen in Germany, just a few miles from the Dutch border. It was reported as 90% damaged.

Lt. Bailey's original Navigator, Lt G.R. "Swede" Swenson, was flying as the lead GH-Navigator with Capt. W.E. Eisenhart's lead crew. A crewman remarked "there go your buddies, Swede."

Sgt Donald F. Geng furnished the following information on the crew loss: S/Sgt Darden sustained a serious back injury as a result of his parachute jump. Lt Fisher also suffered a back injury. The crew landed on the edge of a plowed field and were captured by the Home Guard near Eisenach while trying to reach a wooded area.

Sgt's Geng and Eckert advised that the enlisted crewmen were sent from Erfirt to Eisenach, then Dulag Luft near Wetzlar for interrogation and processing. They were sent to Stalag 13-D at Nurenburg and then participated on the famous march to Stalag 7A at Moosburg. They were liberated by units of the 14th Armored Division on 29 April 1945.

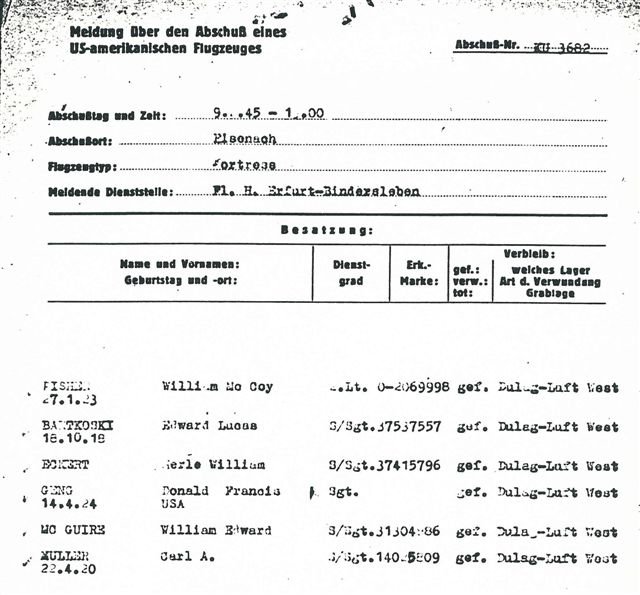

German document reporting the capture of the 2Lt Jack W. Bailey Crew.

THE TRUE STORIES OF STAFF SERGEANT ELWYN JONES DARDEN'S SERVICE IN THE 303RD BOMB GROUP DURING WORLD WAR II

BY BOB DARDEN

Backgrounder

My dad, Elwyn Jones Darden, was a radio operator on a B-17 bomber in the Eighth Air Force in England during World War II. This is an attempt to catalogue some of his stories that he told us when we were kids.

Dad was a member of the 303rd Bomb Group (Hell's Angels) based in Molesworth. His crew was assigned to the 359th Bomb Squadron. His serial number was 34621609.

His crew included: Jack Bailey, pilot; Guy Hall, co-pilot; David "Moose" Johnson, bombardier; Glen "Swede" Swenson, navigator; Carl Muller, top turret/engineer; Billy McGuire, waist gunner; Donald Geng, ball turret gunner; and Merle Eckert, tail gunner. In this photo, dad is first from the left on the front row followed by Muller, McGuire, Eckert and Geng. Second row from the left is Bailey, Hall, Swenson and Johnson.

Bailey, Hall, Johnson and Swenson were 2nd Lieutenants, while the others were "flying" sergeants. Because of a "no-fraternizing" policy, officers weren't allowed to be close-knit buddies with their crews. I came to learn from Merle Eckert that Bailey was able to interview and personally hand-select his crew. That might explain why Swenson and Geng came from Minnesota and Hall and my dad were from Mississippi. Hall was from Greenwood, and Dad was from Hernando.

Training

My dad didn't take too kindly to basic boot camp.

He recalled that the sergeant had given the cadets explicit instructions on how to clean the barracks and make quarters bounce off a perfectly made cot.

One day, during a general inspection, the sergeant donned a white glove and went straight to the rim of the toilet bowl. When the glove came up dirty, the whole cleaning process had to begin again.

. . . read the entire fascinating story here . . . . .

[Transcription Note: The following is a verbatim transcript of a 33-page two-part handwritten manuscript Donald Francis Geng (1924-2011) wrote in 2000 regarding his World War II experience in the U.S. Army Air Force and as a prisoner of war in Germany for the last three months of that war. Don's original strikeouts are as they appeared in his original manuscript; material in brackets has been supplied by me. Thomas W. Geng, January 2016]

On a bright, partly cloudy afternoon in early February 1945, I stepped from a crippled four engine bomber at about 15,000 feet above the ground and headed toward enemy Germany below.

It all started that morning at 6 AM when I was wakened by the Charge of 2 quarters. After washing, shaving and dressing, I went to breakfast and then mission briefing.

Our 8½ hour mission was part of a 1300 bomber force with 800 escorting fights sent to attack targets in Germany. Our target was a synthetic fuel plant located deep in east German territory. Plants of this type were supplying Germany with 70 percent of their fuel and therefore were fiercely defended with 200-300 flak guns (Anti-Aircraft Artillery) and defending fighter air craft.

After Briefing, the flight crews met with the Group Chaplins. I met with the Catholic members. Father gave us Conditional Absolution, Communion and a Final Blessing.

We took off at 9:00 a.m., formed up in our battle formation and headed for Fortress Europe.

Four hours latter [sic] found us at 25,500 feet and on our bombing run. As we neared the target the Flak Guns opened up. The sky all around us was black with bursting shells. After releasing our bombs on the target we turned to head back home. Our two inboard engines received direct hits and were damaged so badly that they had to be shut down. We were at half power, slowing down, losing altitude and had to leave the protective cover of our formation. We were now all along vulnerable to marauding enemy fighters.

We flew on alone for about 20 minutes and then were intercepted by a dozen attacking fighters. The Aircraft Commander (Pilot) ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft.

I was in a free fall and at about 5,000 feet I pulled the rip cord. The parachute deployed and the white nylon canopy blossomed out and stopping my downward plunge. I looked for a possible landing spot and hoped to avoid landing in the trees.

I landed in a plowed field about 200 feet from a wooded area. I collapsed my parachute, disconnected from [the] harness, rolled up the parachute, grabbed my shoes and ran to the woods. I removed my parachute harness, inflatable yellow life vest, flying boots and electric slippers. Put on my shoes and tried to hide the discarded flying equipment in a brush pile. As I started to decide where to go next, I was surrounded by a civilian search party armed with pitchforks. One old man in the party had a rifle which looked very rusty. The pitchforks looked deadly. I raised my hands to show that I was not armed. They took me to a farm house where I was searched and my personal effects were confiscated (wrist watch, rosary, pocket New Testament, and [a] pocket knife) and put into a small bag - except for the pocket knife. The old man seized the knife and and put it in his pocket and would not give it up.

About 3/4 of a[n] hour later two uniformed armed men came and had me pick up the discarded flying gear and was taken on a road that lead to town. On the way we met two men riding a motorcycle with a side car. They were dressed in civilian clothes. They may have been members of the dreaded Gestapo.

They talked briefly with my escorts and one shouted at me which sounded like swearing. He hit me on the back and pushed down, shouting all the time.

Arriving in town, we went to a building that looked like a government building. The escorts had me leave the flying gear in the reception area and took me upstairs to a small office. The office was occupied by a German Military Office and his secretary. The Officer did not speak English but the Secretary spoke very good English. I was asked to sit down at a table and given a paper and pen. I was asked to write my name, rank, Air Force unit, intended target and details of our mission. I wrote my name, rank and army serial number and wrote that I was under orders and as a POW I was not obligated to give any other information. The officer emptied the bag of my personal effects. Asked his secretary about the New Testament. This was [the] Catholic Edition of the New Testament given to me at Basic Training. The officer asked to see my "Dog Tags" (two identification tags worn on a neck chain).

The officer and his secretary looked over my personal effects and returned them to me. I did not see the billfold that contained 25 British Pound Notes. Years latter [sic] it occurred to me that some time between the time of my initial search and confiscated [sic] of my personal effects at the time of capture, and my session with the Military Office, someone probably decided to keep the billfold and paper money.

Our issued escape pouch contained German and French Scrip. A few weeks prior to the last mission, it was suggested that we carry some English paper money for possible use in evasion and escape should we find ourselves in enemy territory.

After returning the New Testament, Rosary, comb, and wrist watch (not a military issued watch), the Officer noticed that I had two small waxed packages in my brest [sic] packages [sic]. I told them that these were fortified chocolate ration bars. The Secretary said that the Officer replied that he has a 4 year old daughter (or maybe grand daughter) that had never tasted chocolate. I handed one of the bars to the officer and said that it was for the little girl. He smiled and accepted the bar. I put the other bar back in my pocket, thinking a half a loaf is better than none.

I asked the secretary the name of the town. She said it was Eisenach. She pointed out the window to a castle which she said Martin Luther was kept there by his friends in protective custody for over a year. While he was there, Luther translated the Bible from Latin to German.

I was then taken to a lock room in the basement where I found five other members from my crew, the Navigator, Front Gunner-toggleier [?], Waist Gunner and the Tail Gunner. They told me that our radio operator landed in a tree and fell while trying to get out of [his] parachute. He injured his back and was taken to a German hospital. This accounted for 6 of the 9 crew. He did not know the whereabouts of the Flight Engineer, Pilot and Co-Pilot.

Later on, we met the Flight Engineer in a Prison Camp. He jump [sic] after us and avoided capture. He wondered around for several days, and could not find anything to eat. Knowing that he was deep in enemy territory he decided to surrender voluntarily at a Police Station in a small town.

*After [the] war we found out that the Pilot sent the Co-Pilot back to the rear of the plane to make sure the other crew members had bail[ed] out. When the Co-Pilot returned to the cockpit, he found out that some of our escort fighters had chased the German fighters away. The Pilot decided that he and the Co-Pilot would stay with the aircraft and try to fly westward and see if they could reach Allied occupied territory. One of the escorts stayed with them, but had to leave because of low fuel. They reached the Holland - Belgium border and put the plan on autopilot and jumped. They met Allied ground forces and returned to England and both finished their combat tours in early April and went home.

The airplane was recovered by an 8th Air Force salvage crew in March 1945. It was about 90 [percent] destroyed.

I took the chocolate bar and broke into six pieces, one for each of us.

That evening we received our evening meal of a slice of coarse brown bread with margarine and a cup of weak beer.

The next day we were fed breakfast, some bread and a cup of imitation coffee.

The guards came and had us pick up our flight gear and marched us through town. Near the rail yards that was bomb[ed] during the night, we encountered a very angry group of civilians. They had captured several British Air Crew that they hung with cords from their parachutes. They were stoning us, cursing us, and wanted to take us. Our guards were Luftwaffe soldiers, well armed and kept the people away. They hurried us to a siding and locked us in a boxcar. Shortly, the car was coupled to a train going east and we went to Erfurt.

We were marched to the Erfurt - Binberaleben [sp?] Air Base. We were relieved of all of our flight gear, helmets and the electrical element liners in our jackets and pants. The loss of the liners meant loss of warmth and loss of our sheep skin flying helmets left us bare-headed.

We were immediately interrogated by a Luftwaffe Officer. I gave him my name, rank and serial number. He wanted my squadron and group identification, home base, intended target, size of the strike force, etc. I told him as a Prisoner of War, I was obligated to give him only my name, rank and serial number. He said he need[ed] the additional information to determine if I was a spy, for which I could be executed. I said that [I] doubted that an American spy would be dressed in a U.S. uniform. Anyway, I would give him no further information. I further said that based on his reasoning, that I would probably be executed whether [I] did or did not give him needed information. In an angry mode he said I was insolent and I would be sent to the Interrogation Center and they had a way to get the information they wanted.

We had a[n] evening meal of their cabbage soup, black bread and coffee (imitation). We we[re] gather[ed] up and give of us were marched back to the railroad yards, put into a box car and went west. We traveled all night, stopping a[t] some times while the train was under attack by British night fighter-bombers. We had only straw in [the] car to lie down, try [to] keep warm and sleep. The hunger, cold and anxiety made it hard to sleep. Even praying was difficult.

We arrive[d] the next morning at Frankfurt/Main and were put on a tram car occupied by Military and Civilians for the journey to the town of Obersural [Oberursel], about 7½ mile[s] Northwest of Frankfurt.

*The destination was the Intelligence and Evaluation Center - Auswertestell West. This large camp consisted of [a] cluster of low barracks type buildings, with [the] largest a "U" shaped building with the solitary cells, and was surrounded by a high security fence. The Center processed all Allied Airmen who operated from bases in England, Italy and Africa.

The building housed a reception area, offices and Interrogation rooms along with solitary cells to house the POWs.

In the reception room we were instructed to hand over our Dog Tags and all personal items except clothing. We were given a card to write our name, rank and serial number. One Dog Tag was removed a[nd kept by the German Clerk and the other tag on its chain was returned to us. My personal items - wrist watch, rosary, New Testament and comb were put in a box along with the card with our name on it.

We were then taken to our individual solitary cell rooms. The cell was about 6 by 10 feet and about 8 feet high. It had a high, single window with iron bars on the outside. The walls between cells were insulated and the room heated by a wall mounted electric heater. There were no ____ [pipes?] between the cells which could be use[d] to communicate between cells. The heavy steel door had a barred window to allow the guards to check on the prisoner. The cell had a bed with straw and one blanket. We slept in our clothes. There was also one wooden chair.

and reinforce the idea that you were indeed a prisoner and subject to their whims and control. It was also designed to capitalize upon your anxiety. The poor food and insufficient number. [prior sentence incomplete; next sentence appears to describe an interrogation] He said that the other information would expedite notification. The form did not specifically say that it was a Red Cross form but at the bottom it said, "Printed in Switzerland" to lead you [to] think it was a Red Cross document. I declined to give any information and said that I thought Germans were pretty efficient people and notification would be timely. He smiled and said that since I would not give any further information I would return to my cel..

A day or two later I was laying on the bed, when a man in civilian clothes was admitted to my cell. He said, "Don't bet up, we are not going to shoot you today." I said, well thats good. He laughed and said "only kidding." He spoke good English with a slight accent. He put out his hand for a handshake and introduce[d] himself as Herry Schmit. He sat down and said he represented the German YMCA. (I did not know if the YMCA was active in Germany or not). He said his visit was to assure that I was well and well treated. I said that I was hungry and the food was poor and sparse. He said that because of war in general and especially our bombing attacks, the German People were also feeling the effects of insufficient food. (He looked well fed).

He then asked me where I was stationed in England, asked me where my home was in the U.S.[?] What did I do before the Air Force.[?] Was I a student.[?]

I told him that I was allowed only to give my name, rank and serial number. I did say I could probably give him by birthday date. (I think I might have put my birth date before, accidentally).

He said that he was just curious and trying to be friendly. He said he had visited a relative in the U.S. before the war. He also said that he could tell by the 7 and 55 in the second, third and fourth numbers in my serial number that I was probably from the Upper Midwest USA. He then got up and said that he had to visit other prisoners.

The next day I was again taken to an Interrogation Room. The Interrogator was a different person. He was friendly, asked me to sit down. Offered me a cigarette. I thanked him said I did not smoke. He asked if I had reconsidered and wished to complete the "Red Cross" information to speed up the notification to my loved ones and expedite reception of Red Cross food parcels. I said no. No additional information would be given. He then said, "well, I guess we are through with you. Within the next few days when we have sufficient numbers of Prisoners, we will send you to Dulag Luft at Wetzler.["] (Dulug Luft was [a] transit camp for Airmen for temporarily holding prisoners before they were sent to their permanent camp or Stalag). He said that upon leaving the Center my personal belongings would be returned to me. He stood up offered his hand and said "Good Luck.["]

Except for the greeting by the "YMCA" man, which was said in jest, was I ever threatened, insulted, or exposed to any unpleasantness at the Interrogation Center.[?] The conduct was psychological. The loss of personal effects, solitary confinement, lack of food all contributed to damaged morale and self respect. The solitary existence with nothing to occupy time was especially difficult and capitalize[d] upon your anxiety. This anxiety itself was a fearful thing. During your captivity, especially the initial period involved the difficult adjustments to the fact that you were a prisoner in a very hostile environment and subject to the control of a cunning enemy and maybe a ruthless one in spite of the general decent treatment at the Center.

Along with insufficient food and opportunity to exercise sleeping was difficult. You had to realize that at a young time in your life that your well being was in the hands of God with no family, friends or U.S. military support. Praying was even more difficult. My prayers were mostly for my family, especially my mother who was in very poor health. Prayed for the end of the terrible war and all the suffering it was calling. [sic]

We did not know about the infamous Death Camps. If we had I am sure our anxieties would have been much greater.

One day a group of us were assembled, give[n] our personal effects and boarded the Tram car and went to Frankfurt under guard to the railway where we went by train about 35 miles north of Frankfurt to the Dulag Luft at Welzar. This was [a] transit camp or distribution center for temporary holding before prisoners [were] sent to their Stalag (Permanent Camp).

The camp was mostly barracks to house the prisoners. Officers were housed separate from the enlisted men. There was a mess hall, library and large meeting area.

The prison compound was governed by a Senior Allied Officer. At this time it was an American colonel, a fighter pilot captured in Italy after his plane was hit by ground fire. He welcomed us and said he would try to help make our stay as comfortable as possible.

Besides the German Food Rations, the camp received Red Cross Parcels regularly. The normal procedure was to give the parcels to individual prisoners or often shared by two prisoners. Because of the transient nature of our stay at this camp, it was decided to merge t he contents of the food parcels at a central kitchen and serve two meals each day. While the quality of the food was better, there was not enough to satisfy hunger.

The camp has a permanent POW staff that ran with compound with the permission of the German authorities. The Allied POW camp staff seemed to get along with their German staff.

The camp was located close to a railroad yard and not too far from a large optical works. The camp roofs were marked POW in large letters. There was some suspicion that the Luftwaffe move[d] Dulag Luft to Wetzler and located the camp to ward off Allied bombing.

It was a very welcome change from the solitary life at the Interrogation Center. The food was better even though not sufficient to satisfy our hunger. We could be outside and exercise when the weather was good. The library had books, playing cards, chess and checker games. The library was staffed by a British Catholic Chaplin who had jump[ed] with a British parachute regiment and capture[d] by the Germans. The story in the camp was that he had escaped three times and recaptured. When you went into the library he would greet you and ask if you want to go to Confession, use the books or games and did you have an escape plan!

During our stay at this camp, the POWs put on a variety show. I don't know where they got the clothing, but some were made up like women. They had band instruments and formed a small band - their theme song was the tune "Time on My Hands," very appropriate!

Weeking [sic] the cigarettes that came from the Red Cross parcels were distributed equally to the prisoners. Even though I did not smoke, I decided to keep my share for barter purposes. We had little contact with the German Guards. The Colonel and a small POW staff ran the compound. The Colonel was a West Pointer, very disciplined and seemed to get along well with our captors. The German Staff came in each morning and we had to line up for a count. In the evening they made a tour of the prisoner's compound to check on conditions. Occasionally, they had a surprise check. We suppose[d] they were losing for clandestine prisoner activities.

The Colonel told us that it was our right to try to escape, but he did not think it wise to try to escape this camp, since we were here only a short time and the Germans were quite cooperative.

After about ten days or two weeks we were [told] to gather our belongings a[nd] line up in [the] yeard for our departure to our Permanent Camp at Nurnberg.

It was a cloudy day and just before leaving, the air raid sirens sounded and we could hear the approach of bomber aircraft. The Colonel told us to lie down in a deep trench along the road leading to the compound gate. From the sound of the planes, they seemed to be medium bombers that were bombing at low altitude. We could hear the bombs hit and explode and the German Flak guns firing at the planes. Since the plans were above the clouds and totally obscured, they must have been bombing by radar. We worried about a stray bomb or bombs just missing the target. After the air raid was over we returned to our barracks. The next day we boarded a train on a siding and headed southeast about 200 [miles?] to Nurnberg in Bavaria. During the night, we stopped several times to avoid traveling when Allied night fighter bombers were looking for train targets.

We arrived on a siding on the outskirts of Nurnberg and were marched to camp. The camp, Stalag 13D, was located less than 3 miles from a large railroad marshalling yard that was a frequent target for the American and British Air Forces.

The Stalag was large but crowded because many of the POW camps in the Northeast sent their prisoners with the advance of the Russian Army toward Berlin. The filthy conditions, lack of food and the anxiety and fear generated by the frequent bombing raids by American and British Aircraft. In late February, on two successive days, the U.S. Air Force unleashed saturation bombing raids. These were fearsome displays of [the] power and destruction of the strategic bombing campaign as seen from the ground. As a member of a bomber crew we had been on the bomb delivery end and could not imagine what it like to be on the receiving end.

One of the risks for us was the falling to earth of spent flak shells [sic] fragments [sic] from the numerous flak batteries near the camp that were firing at the attacking bombers.

These daylight raids also showed us the progress of the bombing formation and inevitable stray aircraft that got separated from the main force. We worried that as these strays passed over us that they would not [sic] release a bomb or bombs that failed to release over the target area.

About a week later at night the British Air Force attacked the rail yard again. The hundred[s] of flak guns firing, the colored flares dropped by the pathfinder planes to mark the target, the searchlight searching the sky, the roar of the approaching bombers, and the deafening noise of the exploding bombs created a frightening scene. You wondered if Hell was like this. You pray for yourself and your fellow prisoners, the members of the British crews flying above, and also for the other people - enemy included. These experiences will remain in your memory for a long time. We prayed that no American city would ever have to endure the terror of aerial bombing.

One night about the first of April, 1945 we were aroused near midnight and told to fall out and prepare to leave the camp. They kept us waiting outside for several hours. Finally, we were allowed to go back to bed. The next morning when we were assembled for prison count, the gate to the compound opened and about 20 U.S. Army prisoners were brought in. We later talked to the new POWs and found out they were part of a tank company that went about 40 miles beyond the battlefront to liberate a POW camp. They got lost during the night and many of the tank force were killed and these were the survivors that were captured.

On April 4, 1945 the prisoners at Stalag 13D were put [on] march with the destination Stalag 7A at Moosburg which was about 20 miles north of Munich. After we had marched about 10 miles, the City of Nurnburg was bombed by heave bombers which were probably from the 15th U.S. Air Force base in Italy. A German guard just shook his head and said, "they are just turning the ruins over." This beautiful city, a city know[n] for the manufacture of toys, was nearly completely destroyed by bombing and later by artillery. (It would be rebuilt after war to its near pre-war architecture.).

Later on in [the] afternoon about 3 pm we [were] attacked by two P-47 American fighter planes. This happen[ed] just as we were entering a small village with a rail yard at this location. I saw them in flight with a third plane which provided high cover for the two attacking aircraft. The two suddenly started a dive and I shouted to my comrades to jump into a deep drainage ditch beside the road. As the planes passed over us the spent cartridges bounced on the road way. There was a railcar with anti-aircraft guns in the rail yard and it was firing at the attacking planes. They may have been really strafing the train and not necessarily the prisoner column. We did hear that some prisoners had been wounded.

We spent the next two weeks on the road leading to Moosburg. The weather started warm[ing] up, and except for rainy days it was nice to be in the country side which was quite beautiful. When it rained we tried to find shelter in barns, but most the time we just got very wet in the wooded areas that provided a little shelter.

The German guards could not feed us so we were dependent upon the food we brought along with us. Before we left the camp at Nurnburg, we were given Red Cross food parcels, one per two men. Along the march we were supplied with parcels by white painted U.S. trucks manned by the Swiss Red Cross. Their leader drove a 1937 Ford Coupe! Sixty horsepower engine! The British POWs seemed very interested in this "Typical American car.!["]

The food parcels were mostly from the U.S. or Canadian Red Cross. A few came from Belgium or Holland. These must have been somewhat old because at this stage of the war, these two countries were short of food.

The parcels generally contain[ed] powdered milk, powdered eggs, can meat or fish (Spam, corned beef, salmon, tuna) sugar, coffee, canned margarine or butter, chocolate and cigarettes.

We found the Germans on the farms and small towns friendly and willing to barter for good bread, fresh eggs and potatoes (that were not wormy) in exchange for sugar, chocolate and cigarettes.

We actually camped at times in order to cook and prepare our meals. Some long time prisoners had cookers they constructed from empty cans. These cookers had blowers powered by wood pulleys, string and cranks. The in[genuity] of people is remarkable. The blowers made it possible to use paper, leafs [and] twigs for fuel and could heat coffee water [in] a very short time. Of course because the metal from the cans was very thin, the part of the cooker at the fire would burn through. They just made new parts from additional can parts.

The people in Bavaria were probably mostly Catholic and most farms and village gardens had little shrines with statues of Jesus, Madonna and Child, the Blessed Virgin Mary or St. Francis.

During the latter days of the March, we were often "buzzed" by American fighter planes. They would rock their wings to let us know they knew we were POWs on the move.

We arrives at Stalag 17A about the 20[th] or 21[st] of April 1945. The camp was overcrowded and dirty. Food from the Germans was nearly non-existent. We had to depend on the food we save on the march to sustain ourselves.

The sanitary conditions were terrible. There seemed to be a lot of _____________.

The POWs in the camp were from many different Allied countries.

The permanent barracks were not sufficient in number to house the influx of all the new POW streaming into the camp from other Stalags. Large circus like tens were erected to house some of the POW. Some POWs joined together to make small "blanket" tents."

On April 28th, we could hear small gun fire and the next day, tanks from the 14th Armored Division of the 3 rd U.S. Army broke into the camp and we were liberated!

The next day, General Patton rode through the camp and greeted us with a big smile.

Year later, I saw the movie "Patton" with George C. Scott as General Patton. There was one scene where Scott is riding, standing up in a jeep reviewing the troops - polished helmet with general's stars, battle jacket, riding britches, polish[ed] boots and ivory handled revolvers. I told my wife about General Patton's visit to the camp at Moosburg and I said, "[h]e looked just like George C. Scott!"

About the 9th of May, we were air lifted to Paris. There we had our first warm shower (first one in three month[s]), new clothing, were paid and debriefed by Intelligence Officers. We billeted in a hotel that was taken over by the U.S. Army and fed in a restaurant that was a temporary mess. The food was wonderful, and plenty of it.

The next day we were taken by truck up to a camp called "Lucky Strike" near La Harve on the Normandy Coast. The Army set up several camps of this type to process the troops that were returning to the U.S. These camps were named after popular cigarette brands - Lucky Strike, Old Gold, Chesterfields, Camel, etc.

A few days after I arrived in camp, I was suffering from nausea. I went on sick call and a medic gave me some pills for my stomach. A couple of days later I mentioned to a soldier that shared a tent that I still did not feel like eating breakfast. He looked at me and said think you have yellow jaundice. He said the whites of my eyes were yellow. I went to the Aid Station and asked to see a doctor. He diagnosed my illness as Infectious Hepatitis, caused by a virus or toxin transmitted by contaminated food or water. They sent me to a field hospital and then to a General Hospital in Paris. I stayed there until about the 1 st of July and then transferred to an evacuation hospital near the Orly Air Field.

On the evening of July 4, 1945 I left Europe on a C-54 hospital plane and arrived at Mitchell Field, Long Island, New York. Shortly after we were settled at the hospital, a Red Cross lady brought a telephone to my bed and I was able to talk to my family - first time for a year.

After a day or two at Mitchell Field I was transferred to a General Hospital in Iowa. After a week or so there, I received a 30 day sick leave and went home. During my stay at home, the war with Japan came to an end on August 14, 1945.

After my leave was over, I reported to an Air Force convalescent hospital at Fort Logan, Colorado. I was Honorabl[y] Discharge[d] from the Army Air force in September 1945.

Epilogue

Fifty-five years after the end of World War II it is somewhat difficult to recall many of things that happened long ago.

Many of the written accounts of Veterans' experiences are all based upon diaries or notes kept by individuals. When you are missing in action, your personal effects are picked up and eventually sent back to the USA and kept in storage for eventual return to the veteran or his next-of-kin. For some reason my written accounts were not included in my returned personal effects.

With probably the exception of returning service men and women who chose to remain in the Service, most Veterans just went home and talked little about the war. Most were anxious to return to civilian life, forget the war and go back to a job or continue with their education.

For many combat Veterans there might be times of re-occurring bad dreams, time of unexplored anxiety and restlessness.

Veterans of the Korean and especially the Vietnam war seem to suffer from what now known as PTS or Post Traumatic Disorder and we now no [sic] that this was present in World War II Veterans.

The effects of PTS can remain with you for years after the war. The fact that you tried to simply forget about the part of service that involved combat and time as a prisoner of war, probably did not help much. The services did do some psyco counseling after repatriation from POW captivity; little was known of the long term effects except for some very disturbed cases.

No concentration of thought or imagination can set the mind for the overwhelming idea that you are an expendable human being with a dark secret that there was an enemy out there that was trying to kill you while you were trying to do your part to prosecute the war to its conclusion. Continued exposure to this action does not dull the senses that you will overcome this fear or anxiety in subsequent action. Safety [?] comes an impossibility and only your preoccupation with your busy assigned tasks acts toward self-preservation.

It is the time after the mission that you have time to think, that really works on your mind.

A particularly had period for a POW is when you are in solitary confinement with no outlet for [a] time.

Do you pray? Yes, when you can. At some time even praying become[s] nearly impossible. You realize that you are not in charge and when a Prisoner even your own military does not control you. You [are] at the mercy of the foe. You are constantly in danger and only your faith really sustains you.

Yes, you do pray at the most difficult times for your well being. During the less immediate times, you pray that you will fullfil your sense of Honor, Duty and be a leader for your comrades in [the] army. You pray that your family will be ok[,], not worry and trust that things will work out. You also pray that the war will come to a quick end and a just peace will prevail. You also pray that war particularly the Air War will never come to your homeland.

You also think and pray for the foe especially for the young and old caught up in the Cities during the bombings.

What are [the] other consequences of your war time experiences?

You hope to return to a peaceful world, find civilian life in some worthwhile pursuit.

You realize the value of family and friends. You work for a strengthened spiritual life.

There is a realization that most of the people in the world simply want to live good, productive lives, want peace and prosperity enough for a happy life. At the same time you are aware of the evil side of many, that seems to want to satisfy his greed for power and material wealth.

Experiences as a Prisoner of War teaches you basic psychology and as a course in human relations.

One final thought. I have been without my wife for ten years. She was my best friend and without her, life at times is very lonesome. At time when I return to an empty house after being away, I find her loss causes a tough lonesomeness. Not having that special person around to love and care for is difficult.

Now and as back 55 years ago, it is faith in God that sustains me.

[German document courtesy of Terry Eckert]