Submissions of 303rd Bomb Group related stories and articles are most welcome.

March 24, 2013

Volume V, Issue 3

www.303rdBG.com

excerpted from the book Berlin to the Gulf of Mexico: Pow 5518 Remembers

by James J. Crooke, Jr.

copyright © James J. Crooke family, used by permission

RICHARD L. CLEMENSEN CREW - 359th BS

(Assigned 359BS: 29 August 1944 - Photo: 10 September 1944)

2Lt Richard L. Clemensen (P)(KIA), 2Lt George S. Burson (CP)(POW),

2Lt James J. Crooke, Jr. (N)(POW), 2Lt Frank W. Stafford (B)(KIA)

Sgt Eugene F. McCrory, Jr. (E)(KIA), Sgt Kurt Schubach (R)(POW),

Sgt Lloyd L. Albern (BTG)(POW), Sgt Nick Kriss (WG)(KIA),

Pvt Jack R. Allerton (WG), Sgt John W. Jauernig (TG)(POW)

The third and final mission of the 2Lt Clemensen Crew was Mission #241, 12 September 1944 to Brux, Czechoslovakia, in B-17G #42-31177, Lonesome Polecat. The formation was hit by seven fighter attacks between 1100 and 1130 hours. Attacks were principally from high on the front of the formation out of the sun. An FW190 shot a hole in the front part of the wing of Lonesome Polecat, close to the No. 3 engine. Strips were flying off the wing. Another attack forced the B-17 out of formation and it slid off and dropped down. The horizontal stabilizer was also hit and strips of metal were coming off. The wing then caught on fire. When last seen Lonesome Polecat was in a glide, about 1,500 feet below the formation, still under control.

James J. Crooke recalled his last flight in his book Berlin to the Gulf of Mexico: Pow 5518 Remembers. Mr. Crooke passed away in January 2013. HIs family graciously agreed to share this excerpt from his book. The book is available on Amazon.com and other online booksellers.

|

Around 1100 hours I sighted enemy fighters at 3 o'clock but still out of range. The intercom crackled with the voices of our crew:

"There they are!"

"They're turning at us "I'll get the SOB!"

Still writing in my log the running account of the events. Checking our position. "Some fifty miles NW of Berlin. All gunners in position."

I stood up from my navigator's table and swung my 50-calibre in the general direction of a Focke Wolf 190 at 2 o'clock high. The top turret and the right waist guns were busy. The FW190 rolled and swept by in a diving turn and out of my sights. I dove for the opposite 50-calibre as Frank, the bombardier, operated the nose guns. Then all hell broke loose.

The Fort became a barn with a tin roof peppered by large hail stones. The Luftwaffe had flown well; their fire had found its mark. A 20mm cannon shell, had torn through our number two engine.

The excited voice of our tail gunner broke the momentary shocked silence on the intercom.

"We're coming apart! Skin is flying off the whole damn ship! I'm getting' the hell outta here."

Time seemed suspended. Everything seemed to move in slow motion. The sturdy ship shuddered and groaned like a wounded dinosaur.

No word from the cockpit. I turned for a last entry — why, I'll never know — in my log:

"Hit by FW190 at 22,000 feet. Controls out."

Then, realizing that we would have to bail out, I screamed through the incredible noise, "Let's get outta here!" Bail-out procedure called for Frank and me to exit the escape hatch on the port side of the craft and for Red, the engineer, to exit the bomb bay doors.

I had already buckled on my chest pack and cut loose my oxygen, for some inexplicable reason leaving on my face mask. Seeing that Frank was having trouble releasing his flak jacket, I turned to help him. He tried feverishly to salvo the bombs, but there was no control of the plane's systems, automatic or manual.

The diving ship made difficult work of any movement, but I struggled to the navigator's escape hatch, where Red was yanking desperately at the release handle, to no avail. Not knowing that the bomb bay doors, too, were jammed, he turned toward the bomb bay doors to exit there. I screamed and grabbed for him but missed. George, the co-pilot, coming forward, also grabbed at him as he passed and attempted to turn him around, but centrifugal force pulled Red away. At the jammed hatch, I began kicking at the emergency handle side with my heavy flying boot.

By then the plane was in a "falling leaf" pattern, and when the hatch finally gave way, centrifugal force prevented my pulling myself through the hatch. George put his feet on my back and pushed while I pulled. Frank, behind George, struggled to maintain his balance. Suddenly the slip stream sucked George and me together into a welcoming sky.

For an incredible few seconds, time seemed to stand still. In slow motion I rolled over and was conscious of a tremendous concussion as our plane exploded directly overhead. Suddenly, a burning Tokyo tank (gas tank) was falling with me just ten feet away. I stuck out an arm and slow rolled in an attempt to maneuver away from it, but the tank was still there. I had visions of my opened chute becoming a butterfly net for a tank with flaming wings.

By now the almost silent rush of denser air had cleared my oxygen-starved brain. I saw the earth begin to move. From somewhere came the measured words of an instructor:

"When you see the earth below you begin to move, pull the rip cord."

I reached for the D-ring with my right hand. It wasn't there. In the confusion of moments before, I had buckled the chute to my harness upside down. Desperately I clawed with both bands and found the handle to my future with the left hand. That gorgeous mushroom of silk held me affectionately. But not for long!

Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf fighters remained in the vicinity, shooting at everything in sight. I had delayed pulling the chute almost too long. One giant swing and my flying boot-covered feet dug into freshly-plowed earth. My bottom, my back and my flak helmet made a good impression on Germany!

Finally removing the long-snouted oxygen mask, I had a fleeting thought that, coming down, I must have looked like an anteater floating under a giant mushroom! I looked for George and saw that he had landed a hundred yards away. There was no sign of the others. I was unscratched, but George had a badly sprained ankle. Remembering the admonitions given at intelligence lectures to shred parachutes upon landing so that they could not be re-used by the enemy, I spied coils of barbed wire and attempted to throw the chutes across the barbs and tear holes in them. Within minutes we attracted quite a group of folks with varied attitudes. Some were uniformed, carrying binoculars and rifles. Others with pitchforks were obviously tillers of the soil. Some spoke threateningly in guttural German. Others, the young and not-so-young girls, fingered the silk parachutes. I guess they were interested in using them to make hard-to-come-by panties and other clothing.

Events had moved so swiftly our minds had difficulty putting it all together. One thing was certain we were not far (some eighteen miles, I figured) outside Berlin. There was little chance of our contacting the Underground. I began to realize that we were to be the uninvited guests of the Third Reich.

A uniformed land army cyclist ordered the two of us to push his motorcycle to the next town. We didn't understand his words, but the open barrel of his Luger communicated his intent.

George's ankle had begun to swell, and he was in intense pain. I told him to just hang on and pretend to push.

George had determination, so this ploy worked, but to this day I don't care for motorcycles.

About two hours later, followed by a coterie of assorted military and non-military types, we limped and pushed the motorcycle over cobblestone streets into a small town as fraus, frauleins and assorted little heads gazed in silent interest at the terror-fliegers bagged for the day.

The town square and the city jail were a welcome sight because here we parked our captor's cycle and went inside. My navigator's hack watch, my black onyx ring, and the tiny compass from the escape kit I routinely carried in a leg pocket of my flight suit were taken from me. We were stripped to our longhandles, frisked, pushed around a bit, ordered to redress and placed in chairs facing opposing walls.

A third captive was brought into our party and placed facing a third wall. We were to learn later that he flew cover, in a P51 Mustang, for our mission and got into the gun sights of a FW190.

As we sat dumb on those chairs, it dawned on me that we had not eaten or had anything to drink since 0330, when we took off from the Molesworth Airfield in England. I became acutely aware of my hunger.

![]()

By Latisha Koetting

The Sedalia Democrat, February 27, 2013

I recently received an email that began,"Hello! My name is Latisha Koetting and I work at the Sedalia Democrat newspaper in Sedalia, Mo. Today I received a call from a young gentleman from New Mexico. Well, actually, he's 94 years old but he's young to me. . . ." Over the past 13 years, Ms Koetting has worked with veterans from all over West Central Missouri documenting stories about their military service. We are pleased that Van is now included in her 300 published veteran's stories.

|

White enlisted in the service long before the Pearl Harbor attack took place. In October 1940, he was visiting a high school classmate in Indiana. He was told everyone of age had to register for the conscription (draft).

“I had heard about the war in Europe, but I didn’t know the United States was going to get involved,” he said. He registered in Indiana. A week later, he was back in Missouri. He went to the barbershop one morning with a classmate. They decided to enlist in Sedalia, so they could pick their branch of service. He chose the Army Air Corps, because he loved airplanes and had worked at the Kansas City airport after he finished high school in Smithton.

Ten days later, he took a train to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis.

“My class A uniform came out of moth balls from World War I — the super blouse, like the doughboys wore in WWI, with the wrapped leggings. They took my shoes out of storage and they had green mold on them. They’d been in storage there 10 years, but that’s what they gave me to wear,” he said.

He was put on a troop train and sent to Langley Field, Va. When a young lieutenant saw what he was wearing, he immediately approached him. “Where did you get this outfit soldier?,” he said. White told him it was his class A uniform. The lieutenant told him to report back at 9 a.m. the next morning and they presented him with a brand new one.

|

“After three times of cleaning up after me, I ended up as a chair-borne trooper in the paragraph corps,” he said. Because he took typing in high school and could type 40 words per minute, he was chosen for administration. In the summer of 1941, he was sent to Westover Field in Mass.

“In those days, even though we were in a heavy bomb group, we only had one airplane. All the flight officers and flight personnel, they had to get flying time in so they would take turns,” he said.

One of his responsibilities was to schedule and keep track of the flying time for the different crews.

The attack of Pearl Harbor took place on Dec. 7, 1941. No one knew what was going to happen next. White was given more responsibilities and in January 1942, he was promoted to sergeant. He eventually was sent to Gowen Field in Boise, Idaho. That’s where he met Jack Snell, of Sedalia.

“Jack was on a flying crew as a tail gunner. We always managed to go to chow together and we became pretty good friends. I didn’t know him prior to the service,” White said.

Ross C. Bales was the captain of the 10-man crew Snell was a part of. Because Bales was from Idaho, he named their B-17 FDR’s Potato Peelers Kids.

|

On Oct. 16, 1942, he boarded one of the new B-17s. They had to land in Gander Lake, Newfoundland, because of bad weather. Six weeks later, they were reunited with the ground crews.

“We arrived in Prestwick, Scotland, after a 10-hour flight from Newfoundland. That was when I got the taste of British food — mutton and Brussels sprouts. I can’t stand either one of them today,” White said.

The German submarines were sinking all of the boats with food for the troops.

“Needless to say, that was one of our first targets on the French coast,” White said.

He spent the entire war at the Royal Air Force base in Molesworth near Cambridge in England. They received their field orders from the Eighth Air Force in London on the teletype. The orders included the target and how many planes were needed to complete the mission. White was one of the men who briefed the crews before and after each mission.

“After the briefing of what the target was going to be and what altitude, I’d see the guys go behind the plane and vomit because everybody was scared to death. They were so apprehensive. It didn’t matter if you were enlisted or commissioned officer, you had the same feeling,” White said.

The men became a close knit family. Each aircraft had a crew of 10-men with four squadrons in each bomb group.

“I remember one mission in particular later in the war when we went deep into Germany. We sent 44 planes and lost 11. That’s 110 men. It takes a long time to replace those crews and train them. It was not easy,” he said.

In England, he remained good friends with Snell. They both were dating girls from Sedalia.

“We used to compare notes and things that were going on in our absence. It just became a really close friendship,” he said.

Snell loved his hometown of Sedalia. After he graduated from Smith-Cotton in 1937, he worked in the circulation department at the Sedalia Democrat. He had the paper mailed to him while he was in the service. Often times, he’d receive two or three at a time because they had an APO number.

According to the Sedalia School District 200 website, Snell sent a picture of the FDR and its crew home to The Sedalia Democrat on May 13, 1943, with information that they had been bombing Axis territory in Europe, namely Nazi held factories, munition plants and other objectives within France.

“The hardest part was sending these guys out to difficult targets when we knew their chances of survival were not too great,” White said.

On May 14, 1943, Snell and the FDR crew were sent on a bombardment mission to Kiel, Germany. The FDR was last seen on its return trip to base going down into the North Sea. None of the men survived.

During this time, the Sedalia Democrat was still being delivered at Molesworth.

“When Jack was missing in action, the newspaper from the Sedalia Democrat gave an account of the mission and Jack’s mailing label was right over the bottom of the picture. It kind of made your skin crawl,” White said. “I think records today would show they probably drowned at sea.”

White stayed in England for two more years. He came home in June 1945 on the Queen Elizabeth I.

“It was not a joy ride, believe me. There were 18,000 GI’s on QEI coming home from England. State rooms, made to accommodate 2 to 3 people, had 8 to 10 people in there. That was not a luxury trip,” he said.

Seventy years later, White still thinks about Snell. When he returned to Sedalia, he tried to get in contact with Snell’s mother but he wasn’t successful.

“I just wanted to rap with her,” he said.

White will be 94 in April and was recently told he was the only surviving classmate of the Smithton class of 1937.

“It gives me kind of a sinking feeling. There’s no place to go, there’s no place to hide,” he said as he laughed. “I’m just glad I was a part of it. I feel privileged to still be here.”

By Randy Kenner

The Knoxville News-Sentinel, Sunday, May 24, 1998

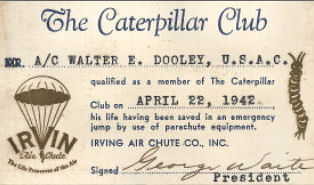

The two-minute video above is a tribute to Walter E. Dooley made by his niece, Rebecca Dooley. The last half includes his broadcast on ARMED FORCES RADIO in February 1943. Dooley became a member of the Caterpillar Club while still in flight training, when his landing gear failed to open. Thanks to Rebecca Dooley for all the photos and information in this tribute to her uncle.

It's a holiday sometimes known more for its cookouts, big movie openings and weekend trips than for its solemn ceremonies. But Memorial Day has been a day for honoring fallen soldiers since the 19th century. Which is why it's the most important holiday for someone like Walter Dooley.

On May 13, 1943, Dooley had just co-piloted a B-17 Flying Fortress on a raid over France so uneventful that a crewman reported, "We could have slept or played cards."

At the time Dooley was 22 years old, a Knoxville native who was his father's youngest son, a faithful friend to a trio of buddies he'd known since junior high and a good-natured, handsome man to a female cousin who adored him.

He was also two semesters shy of an engineering degree from the University of Tennessee and so extraordinarily lucky that he had parachuted to safety from a plane on one occasion and helped bring a bullet-riddled one home on another.

BALES CREW - 359th BS

FDR's Potato Peeler Kids 42-5243 (BN-P)

(Back L-R) Capt Ross C. Bales (P)*, 2Lt Walter E. Dooley (CP)*,

2Lt Paul W. Thomas (B), 2Lt Richard C. Browning (N)**

(Front L-R) Sgt Homer W. Perkins (WG), S/Sgt Raymond K. Winter (E)*,

Sgt Jack D. Snell (TG)*, S/Sgt Raymond H. Kilgore (R)*, S/Sgt Joseph G. Zsampar (BT)*

* KIA on May 14, 1943 — ** KIA 31 March 1943 flying with the Keith Bartlett Crew.

But less than a day later, on May 14, Dooley and the 10 man crews of roughly two dozen unescorted American bombers were fighting for their lives above the North Sea after a raid on the submarine pens at Kiel, Germany. "I remember there were about 40, probably 40 fighters attacked us," Irl Baldwin of Albuquerque, N.M., said. "As I recall, they met us over the water and followed us all the way home."

Baldwin was an Army Air Force captain who was leading the formation in his plane, "Hell's Angels." At the other end of the group, Lt. William J. Cline was flying just ahead of the last plane in the formation, "FDR's Potato Peeler Kids," piloted by Ross Bales and Dooley.

Cline, who now lives in Bakersfield, Calif, no longer has a clear memory of what happened that day, but his diary entry for it notes his plane dropped its bombs at 12:02 p.m., "and things started to happen. Running fight for an hour or so."

Walter Dooley grew up as the youngest of four children in a house on Cumberland Avenue near where a gas station now stands. The Dooleys were, by the standards of the Great Depression, fairly comfortable. Walter's father, Charles Dooley, had a good job.

Sam Fincannon, who met Walter Dooley in the early 1930s at Boyd Junior High School, said, "He was a happy-go-lucky guy, and he made pretty good grades."

Dooley and Fincannon were also good friends with Ed Dougherty and Charles Benzinger during junior high.

"Ed and Walter and Sam and I ran around together," said Benzinger, 77, the only one of the group who still resides in Knoxville.

The four, all 1938 graduates of Knoxville High School, went on to UT.

"He was so handsome, and I was just kind of ga-ga over Walter," said Ann Dooley Parsons, who was about seven years younger than her cousin.

Her family lived nearby on Clinch Avenue.

"We would go over every Sunday night and just have a family supper in the kitchen over there," Parsons said. "(Dooley) loved to read," she said. "I can remember when we went over there on those Sundays, he'd always (have) his nose in a book"

And she remembers model airplanes in Dooley's room upstairs.

The Dooleys had two cabins near Townsend, which was where Dooley and his friends spent every summer moment they could. "There was a field where they'd play softball, and there was always swimming in the river," Parsons said. There were other activities the boys were interested in: "We just hiked and usually there were a few girls around and we went out with them," Benzinger said.

"We chased girls, but we didn't catch many of them," is how Dougherty, now a Nashville resident, recalls it. When the group arrived at UT, their social lives tended to revolve around the fraternity three of them joined, and they shot pool at a hall on Cumberland.

But their world was about to change. Much of the world was already at war by 1939, and the little group of friends knew they would probably be drawn into it.

"We thought we were going to be heroes and all that sort of thing," Dougherty said. "It seems to me, as I look back on it, that Knoxville was sort of a country town back then. And we were sort of country boys. The war was the biggest thing to come along, and we wanted to be in it."

Dooley was the first to go, which broke up the group forever.

"He just all of a sudden went in," Benzinger said.

No one had a chance to say goodbye, and after the war started, each had only a vague idea where the other was, though everyone knew Dooley was somewhere in England. "He wrote us a note about his new plane," Fincannon said.

In late 1942, after training in Texas, Dooley was assigned to the 303 "Hell's Angels" Bombardment Group, which flew out of a base in Molesworth, England.

It was a dangerous place to be. Nearly all the pilots were in their early 20s, and the losses were horrendous. The group flew without fighter cover early in the war, and at least 24 of the original 50 pilots had been shot down by June of 1943.

Dooley nearly shared their fate in a January 1943 raid over Germany in which his plane was so badly damaged he had to get a new one. In a radio interview after the incident he said he was, "anxious to go after them again."

Robert L. Cunningham of Knoxville joined Dooley's squadron months later. At the base, he recognized his friend from Knoxville High in a photograph on a wall before discovering Dooley was already gone.

"You had a job to do, and you did it," Cunningham said. 'Everybody was scared, (but) nobody would admit it."

Walter Dooley was on his 16th mission on May 14, 1943. He was back from a recent leave in London and had written home, telling his parents of his pleasant rest. He and Bales were "Rear-End Charlie" that day, meaning they were the last plane in the group. They were part of a four-plane formation led by Capt. Jack Roller with Cline flying to Roller's right as they cruised toward Kiel, along with five other groups of B-17s in what was the biggest raid of the war up to that time.

Roller, who now lives in Petaluma, Calif, and Cline both remember Bales, and they vaguely remember Dooley's name, but not the person. "Bales was a big guy from Idaho, a farmer," Roller recalls. "Bales was a real nice guy. I'm sure Dooley was, too, but I just don't remember him."

They never got a chance to know him better.

Lt. Col. Harry D. Gobrecht, a pilot and the squadron's historian, wrote in his book, "Might in Flight," that the bombers were met by 100 to 150 German fighters. A running battle ensued that lasted through the bombers' run on the target and most of the return flight to England.

Dooley's plane was in the thick of it, and Cline chronicled the result in stark sentences.

"Bales ... got his left stabilizer (the left horizontal section of the tail) shot up," Cline wrote in his diary. "He was Rear-End Charlie' about 50 miles off the coast, got hit by a (fighter). Seven chutes and he ditched ... blew up in the water."

No one was recovered.

The news hit the Dooley family hard. Within a year, father Charles died of a heart attack.

"Everybody in the family credited (his father's death) to the sadness of Walter's being missing," Ann Parsons said. Benzinger and Dougherty didn't find out what happened until they got home. Fincannon, in the Pacific theater, learned in a letter from his family.

"As far as I was concerned, he was one of the unsung heroes of the war who went out and did his share, and he died," Dougherty said.

He said all the group went to war but, "Dooley was the only one who got killed."

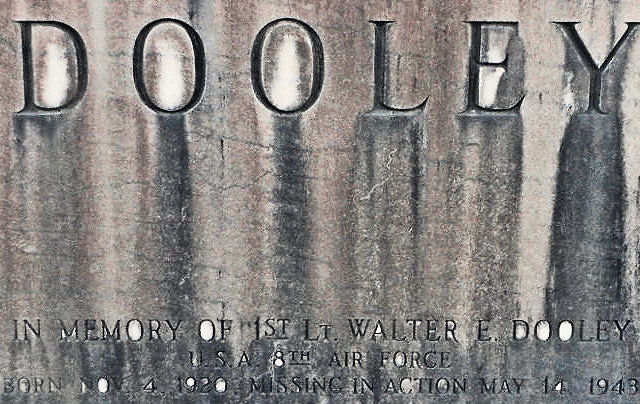

Walter Dooley's monument rises waist-high above the clipped grass of Greenwood Cemetery near the graves of his parents, although no body rests beneath the stone.

The drone of a lone airplane slowly passing overhead and the muted hum of traffic on nearby Tazewell Pike break the silence of a hot Thursday in May.

On the monument a simple eulogy is carved. In memory of

1st Lt. Walter E. Dooley; U.S.A. 8th Air Force; Born Nov. 4, 1920. Missing in

Action May 14, 1943.

![]()

by Peter G. Park, RAF Molesworth Historian

Are you a war bride, the husband, or child of a war bride? Or otherwise related to a war bride? Your experiences and insights can inform a new study.

The American Air Museum in Great Britain (a part of the Imperial War Museum) is doing a new study on British war brides and the researcher, Researcher Alyson Mercer has developed a questionnaire based on one used in earlier studies and would really appreciate if she could get your input and comments. There are 4 versions:

- British War Bride living in the United States

- Family of British War Bride living, or did live, in the United States

- British War Brides living in the United Kingdom

- Men married to British War Bride living in the United Kingdom

"National Designation" and is now the

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE

MIGHTY EIGHTH AIR FORCE

National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force

175 Bourne Ave., Pooler, Georgia

|

— Historic Issues Revisited — This Month: July 1981 |

|

Home of the 303rd Bomb Group (Heavy)

Veterans and family members of the 303rd Bomb Group are able to visit the home of the 303rd at RAF Molesworth located near Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, England some 80 miles northwest of London.

Veterans and family members of the 303rd Bomb Group are able to visit the home of the 303rd at RAF Molesworth located near Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, England some 80 miles northwest of London.

As RAF Molesworth continues as an active U.S. Base today with an important mission, admission to the base is necessarily strictly controlled for security reasons. 303rd family members wishing to visit may contact the base historian Mr. Peter Park at peter.park@jac.eucom.mil who can advise on military entry procedures, information needed from potential visitors, and possible visit dates. |

SAVANNAH, GA - July 22 - 26, 2013

See the details here

Raymond M. Miller, 87, of Hasbrouck Heights formerly of Jersey City passed away on March 6, 2013. Born in Jersey City on March 9, 1925 to the late Charles and Bessie Miller. He was an Army Air Force veteran of WWII.

Raymond M. Miller, 87, of Hasbrouck Heights formerly of Jersey City passed away on March 6, 2013. Born in Jersey City on March 9, 1925 to the late Charles and Bessie Miller. He was an Army Air Force veteran of WWII.

Before retiring, Raymond was a fireman for the Jersey City Fire Department for thirty-five years. Raymond also had his own painting and carpentry business for more than forty years.

Beloved husband of Gloria (nee Torsiello) Miller. Devoted father of Raymond Miller and his wife Anna of Fair Lawn, Linda Coca of Bergenfield, James Miller of Hasbrouck Heights, Judy Collins of New Milford and the late Charles Miller and his wife Mary of Kearny and the late Pamela Miller. Dear brother of Jean Miller of Manasquan and the late Melvin, Douglas, Donald, Alan and Marilyn Ward. Loving grandfather of Christie, James, Briana, Melissa, Charles, Tim, Stephanie, Allison, Greg, Tiffany and Robert. Cherished great-grandfather of Meredith.

Funeral Service at Costa Memorial Home Boulevard and Central Ave. Hasbrouck Heights on Monday at 11:30 AM. Cremation following at Cedar Lawn Crematory. Visitation, Sunday, 2-5 PM. In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions to the American Diabetes Association would be appreciated. www.CostaMemorialHome.com

William S. Hart, 91, of Markleville, passed away on Feb. 26, 2013, at the Marquette Manor Health Care Center.

William S. Hart, 91, of Markleville, passed away on Feb. 26, 2013, at the Marquette Manor Health Care Center.

He was born on Feb. 24, 1922, in Washington, Ind., and resided most of his life in Markleville.

William enlisted in the United States Army Air Force in January of 1942. He served as an aircraft maintenance technician and crew chief at Molesworth Air Force Base in England with the 360th squadron, 303rd (H) Bomber Group, 8th Air Force Division. In 1944 the 303rd received the Presidential Unit Citation for their exemplary service leading a bombing campaign over Nazi Germany. During World War II he also participated in campaigns in Northern France, Rhineland and North Africa, as well as supporting the effort at Normandy on D-Day. After the war was over he was assigned to the Strategic Air Command (SAC) in Nuremburg, Germany, to help with the European rebuilding effort.

During the Korean conflict, he was stationed in Japan with the 35th Fighter Wing, FEAF. After the Korean conflict was over he was stationed at Castle Air Force Base as part of SAC, where he was an aircraft technician for B-52 bombers. Mr. Hart received numerous commendations throughout his illustrious military career. He retired from the United States Air Force as an E-7 Master Sergeant, after 21 years of distinguished service, in 1963.

He worked at Delco Remy, retiring in 1984, and was a member of the Markleville Masonic Lodge 629.

William is survived by his children, Bill (Joellen) Hart of Kokomo, Marie (Butch) Mercer of Indianapolis, Loretta (Darius) Greer of Carthage, and Helga (Gayle) Bridges of Hot Springs, Ark.; eight grandchildren; seven great-grandchildren; companion and family friend Mary Adams of Chesterfield. Several nephews and nieces also survive.

He was preceded in death by his wife, Else (Engelbrecht) Hart; parents, James Harrison and Etta (Gilley) Hart; and three sisters.

Visitation will be from 4 to 8 p.m. Friday at Robert D. Loose Funeral Homes and Crematory, Anderson. Masonic services will be conducted at 7:30 p.m.

Services will be at 2:30 p.m. Saturday at the funeral home with the Rev. Brian Dwiggins officiating. Burial will take place in Arlington National Cemetery.

Memorial contributions may be made to Alzheimer’s Association or Wounded Warrior.

![]()

I was so happy to see the story about Robert Sorenson in the newsletter. I called him "Daddy Bob" after he married my mother. He was a WONDERFUL husband to her, and my sisters and I LOVED him so much. He came into our lives and helped us tremendously. I got to see my mother get the love and attention that she had never been given before, and I loved hearing about the 303rd from him. I still miss him every day, but someday he will be showing me around heaven and introducing me to his friends and fellow 303rd members there.THANK YOU

Tom Beard

Houston Texas

Keeping the Legacy Alive,

|