Febuary 14, 2010

Volume II, Issue 3

www.303rdBG.com

Then rode “The Mustang”

By Freddy Burdeshaw

Earl N. Thomas is one of a rare breed these days, even among the many rare breeds of “The Greatest Generation“--the Americans that won World War II, and established the United States as a superpower.

Earl N. Thomas is one of a rare breed these days, even among the many rare breeds of “The Greatest Generation“--the Americans that won World War II, and established the United States as a superpower.

While helping to defeat Adolf Hitler and his NAZI cronies in that awful war, Thomas piloted 33 strategic bombing missions in the venerable B-17 “Flying Fortress” bomber; this qualified him for a ticket home from the fighting in Europe. At that time, bomber crew members were commonly relieved and sent back to the States for softer duties after completing 25 missions.

Earl Thomas is an uncommon man. Instead of accepting more relaxed work back in the safety of the homeland, Thomas took the very unusual step of volunteering for more combat, this time flying the great P-51 “Mustang” fighter. He eventually flew ten combat missions in that aircraft into Germany!

The 88-year old Thomas, a resident of Peachtree City, settled in the metro area when he hired on with Delta In 1949. He and wife Patricia, have three daughters, Kathleen, Deborah, and Mary who live on the northside. His son John also lives in Peachtree City.

After World War II and separation from the Army Air Force in 1946, Thomas hired on as a pilot based in New York City flying with Trans-World Airlines. This began a rewarding two years making international flights to Europe and the Middle-East. He then moved to Atlanta when he became a pilot with Delta Airlines. He would spend 32 years with Delta before retiring. Thomas said, “I have nothing but praise for Delta, the many different types of planes I flew with the company, and its management.”

After World War II and separation from the Army Air Force in 1946, Thomas hired on as a pilot based in New York City flying with Trans-World Airlines. This began a rewarding two years making international flights to Europe and the Middle-East. He then moved to Atlanta when he became a pilot with Delta Airlines. He would spend 32 years with Delta before retiring. Thomas said, “I have nothing but praise for Delta, the many different types of planes I flew with the company, and its management.”

Growing up in Roanoke Virginia, Thomas was a high school athlete with considerable potential; he played football, basketball and baseball. “I was the jock in the family,” he said. “My older brother was the brains, being valedictorian of our high school which graduated 900 students that year.”

Thomas has continued sports throughout his life, especially golf. Last summer, he was still winning a “semi-annual” Stableford tournament at the Canongate course. A few years back, he was four-time club champion at the old Lakeside golf club. He won the inaugural club championship staged at Lakeside and the very last. He retired the trophy when Lakeside closed, and it is displayed on a shelf in his apartment. Thomas has literally shot his age or better hundreds of times.

During his military service Thomas continued to play basketball and baseball on base teams. It was shortly after the beginning of World War II in 1939, that Thomas unwittingly took the first step toward the military and joining the big fight; of course, neither he nor anyone else could anticipate when and if the United States would become involved.

“I joined the Army National Guard in January 1940, just trying to make a few bucks.” Thomas said, “Like most people during the Great Depression, I wanted to make a little money somehow. The Guard was paying a dollar every drill night which was once a week.” The path Earl Thomas was to take in the coming years proved to be remarkable.

His Guard unit was called to active duty in September 1940 and assigned to providing coastal defense in the area of Hampton Roads, Virginia. As a young corporal, Thomas’ duties included man-handling 155-millimeter artillery projectiles that weighed 95 pounds; he soon had his fill of that.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Thomas decided he wanted to spend the war flying, so he applied for duty as an aviation cadet. After passing the necessary tests he was accepted, thus beginning his life’s work as a pilot.

Over the next couple of years, various phases of flight training took Thomas to stops in Miami, Florida; Montgomery, Alabama; Jackson, Mississipi; Columbus, Ohio; Pyote Texas, and Alexandria, Louisiana. Thomas earned his commission as a Second Lieutenant and his pilot‘s wings in May of 1943. The day approached when he would ship out overseas and join the great crusade.

In December, 1943 he went to Grand Island, Nebraska and took possession of a Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress.” He would fly the big plane across the Atlantic to the European Theater of Operations--England.

In December, 1943 he went to Grand Island, Nebraska and took possession of a Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress.” He would fly the big plane across the Atlantic to the European Theater of Operations--England.

The B-17 was a four-engine heavy bomber used by the U.S. Army Air Force and the 8th Air Force in the daylight precision strategic bombing campaign of World War II against German industrial, civilian, and military targets. Its maximum speed was 287 mph and its range was 2,000 miles. From its belly was dropped more bombs than from any other U.S. aircraft in the war. When the first copy rolled out for its initial flight, bristling with many machine guns, a reporter had called it a “Flying Fortress.” The name stuck. The plane was immortalized in movies such as “Twelve O’Clock High,” starring Gregory Peck.

Thomas landed what he thought was “his” Fortress in Scotland after ferrying it from Nebraska. He was surprised that the aircraft he had flown across so many miles of ocean was not going to be assigned to him any longer. In fact, after he checked in with his permanent unit at RAF Molesworth, Cambridgeshire, England, he learned standard practice was for aircraft to be randomly assigned on a daily basis. No crews had “permanently assigned planes.”

At Molesworth, Thomas was assigned to the 360th Bombardment Squadron, which was one of four bomb squadrons in the storied 303rd Bombardment Group (Heavy), the “Hell’s Angels” Combat Team. Its historic achievements are well portrayed by, among many others, the distinguished aviation artist Keith Ferris.

The very first combat mission that Thomas piloted took place February 4th, 1944, and it was one of his most memorable. He and his ten-man crew took off in a B-17F nick-named “Doolittle’s Destroyer” with a load of over 5,000 pounds of bombs they would drop on a target at Frankfurt, Germany.

Thomas was to fly a number of missions in the B-17F model. But, most of his combat flying was in the B-17G version of the aircraft which included a vital modification. More guns were added under the nose in what was called a “chin turret.“ This was necessary because the Fortresses had been vulnerable to head-on attacks by Luftwaffe fighters. The G-model was armed with a total of 13 50-caliber machine guns.

To his dismay on that first mission, Thomas’ aircraft developed engine trouble--a malfunctioning supercharger, the device that improved power in the thin air of high altitude by forcing compressed oxygen into the engine. This was a perilous development.

Thomas had problems keeping his bird in the formation with the other planes--an arrangement known as the “combat box.” Sometimes called “the battle box,” the formation allowed the Fortresses to protect one another with their combined defensive firepower against hostile German fighters.

“I fought desperately to prevent that plane from becoming “a straggler.” Thomas said, “I already knew the odds were against “stragglers” returning to England. Stragglers were planes that couldn’t stay in formation because they had been damaged, or were having engine trouble. I was just trying to stay alive. You survived by staying in formation”

Second Lieutenant Edgar Miller would co-pilot with Thomas on 16 missions before he qualified to pilot his own plane. He was an observer that day on Thomas’s first mission as pilot. “I was more scared on that mission than on any other I flew during the war,” said Miller. “ We were in that F-model plane with no chin turret guns, and fighters made eight or ten passes at us head-on. Being just an observer, there was nothing I could do to fight back, and that was agonizing. Tommy talks about that supercharger being a problem, but mainly I remember those fighters!”

While the box formation offered safety, it also had its drawbacks because forming all the planes up in the air extended the flying time of a typical mission. Thomas said, “It would take an hour or an hour and a half for the entire box to form sometimes.”

Throughout the war, Thomas and his crew avoided the fate of many other flyers that were shot down, killed, or seriously wounded. Early B-17 losses had been as high as 25 per cent on average, and when attacking some targets the loss rate was even higher. Fortunately, the aircraft that Thomas piloted never lost more than one engine at a time, and his planes were never damaged enough by the enemy to jeopardize his life or the lives of his crew.

“For me, the worst part of flying combat was the sight of other B-17s being shot down or blown up in mid-air.” said Thomas, “Many guys were unable to parachute to safety. I never saw a single B-17 go down where all the crew members got out.”

In March 1944 Thomas was promoted to First Lieutenant and flew 114 hours of combat missions, sometimes flying four or five days in a row. The most harrowing missions were the nine he flew to Berlin.

“Those flights lasted over nine hours, in the very cold conditions of high altitude, and through extended periods of thick flak in the well defended Berlin area.” Thomas said.

The mission on the 6th of March was probably the toughest of all as around 100 Messerschmidt 109s and Focke Wulf 190 fighters swarmed around and through the formations. Thomas said,”We lost more planes and more men on that mission than on any other.”

"The only good thing about those Berlin trips was that the Luftwaffe fighters would not come after us while we were over Berlin flying through flak.” Thomas said, “They didn’t like flak any more than us.”

“Flak” was jagged pieces of metal from exploding anti-aircraft fire. It caused enormous damage to planes that were hit; bomber losses to flak were heavy throughout the war. Thomas said, “With all the noise from the aircraft engines, if you were close enough to hear the explosions, you knew your aircraft had been hit.”

By late April 1944, Thomas had earned a position as a lead Crew Pilot. He eventually completed 33 credited combat missions in the Fortress. After taking part in the pre-D-Day bombing, he flew his last B-17 mission in the aircraft known as “Sack Time”-- bombing oil refineries in Hamburg, Germany on June 20th 1944.

The attack on Hamburg required an extraordinarily long bomb run of nine and one half minutes at low speed, in clear weather--a hazardous situation. Many planes were repeatedly hit by flak but they continued to bore in on the target and dropped their bombs with high accuracy.

Thomas, by then promoted to Captain, received his second Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in the Hamburg mission. Due to his competence as a pilot and his leadership, all of his original crew completed their combat tours without injury.

“Tommy was the best pilot I ever knew!” Miller said. “ He was a natural pilot. He taught me everything I knew in those 16 missions I flew with him. He was just tremendous--very gutsy. When we were taking evasive action from fighters, he put that B-17 into positions where you wondered if we would come out of it.”

According to Miller, Thomas always wanted to be a fighter pilot. After his last flight in B-17s with the 360th, Thomas transferred to the First Scouting Force at Steeple Morden Airfield to fly the P-51 “Mustang.” Thomas was among the first bomber pilots to join the first of the experimental P-51 reconnaissance units.

According to Miller, Thomas always wanted to be a fighter pilot. After his last flight in B-17s with the 360th, Thomas transferred to the First Scouting Force at Steeple Morden Airfield to fly the P-51 “Mustang.” Thomas was among the first bomber pilots to join the first of the experimental P-51 reconnaissance units.

The North American Aviation P-51 was a long-range single-seat fighter. It was fast, well-made and highly durable. It was armed with six 50 caliber machine guns. Its maximum speed was 437 miles per hour and with external fuel tanks, its range was 1, 650 miles. It gained fame for its role as an escort for strategic bombers going deep into the German heartland--the only fighter suitable for such long missions.

Thomas learned to fly the P-51 in only a week and began flying reconnaissance missions in four-plane formations. Their mission was to fly ahead of the bomber groups and provide reports on weather conditions and enemy defenses. Two “Mustangs” would be flown by experienced fighter pilots, the other two by ex-bomber pilots like Thomas. The ex-bomber pilots were needed in the Scouts because they best understood what was required for the bombers to penetrate the European weather conditions.

On one “Mustang” scouting mission, Thomas was to lose a fighter pilot wingman who developed engine trouble, over Germany. Thomas said, “He asked me to give him a heading for neutral Switzerland which was not too far away. I never found out what happened to him. It was very rugged terrain.“

After ten P-51 missions in September 1944, Thomas volunteered for formal P-51 fighter pilot training back in the states. But it was not to be; “the needs of the service” prevailed and because of his bomber experience, he was required to become a B-17 instructor pilot at MacDill Air Base in Tampa, Florida.

After a short stint at MacDill, Thomas transitioned to duty as a B-29 “SuperFortress” instructor pilot. This new, pressurized successor to the B-17 had the range for long Pacific missions. Later, the “Enola Gay”--probably the most famous B-29 of all--was piloted by Paul Tibbets to deliver the first atomic bomb strike on Hiroshima, Japan that ended the war.

When the war was over, Thomas remained on active duty until the summer of 1946. He spent his last days in the Army Air Force ferrying B-29s to their last resting place in “the bone yard” at Davis-Monthan Air Base near Tucson, Arizona. That was then.

Thomas and his calico cat “Baby” recently entertained a visitor in their apartment and he spoke of his part in the long-ago, big battles with the Luftwaffe over the skies of Europe. In those years, all Americans generally understood what was happening “over there.” Today, precious few Americans understand what happened there back then. Even fewer Americans can say they were actually there, like Thomas.

Earl Thomas is now in the middle of another big battle. He suffers from cancer and is under-going chemotherapy that saps his strength and his energy. Nevertheless, as he firmly told his visitor, “I plan to win this battle and be back on the golf course by April.” The visitor left believing every word.

![]()

January 1944: Ground Crew of 358th BS B-17F #41-24562 "Sky Wolf"

March 31, 1945: Something interesting has caught the attention of Major Melvin T. McCoy

and General Spaatz, as well as several onlookers.

Target: Port Area, St. Nazaire, France

Crews Lost: Capt William H. Breed and 1Lt Lawrence G. Dunnica

|

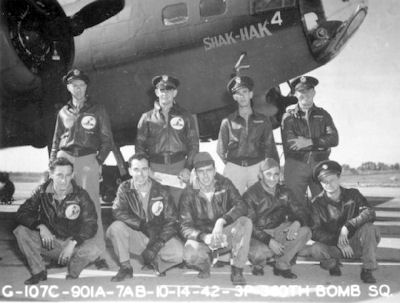

Thirteen Group B-17s bombed the primary target from 25,000 feet with 31 3/4 tons of 500 and 1,000 lb. bombs. Many bomb bursts were observed in the target area, which was covered with smoke and fires. Some bursts were observed in the water. Moderate black and red flak was encountered. Twenty to fifty enemy aircraft were seen, and there were 100-137 attacks. Gunners claimed fifteen aircraft and were credited with four destroyed, one probable, and one damaged.

B-17F #42-2967, Shak Hak, piloted by Capt William H. Breed, was shot down by enemy fighters and ditched on the Brest peninsula. All of the crew of Shak Hak were lost. Killed were Capt William H. Breed (P), 2Lt Harry T. Sample, Jr (CP), 1Lt Homer R. Allen (N), 2Lt Homer N. Santerre (B),T/Sgt Stanley Putala (E)(KIA), T/Sgt Joseph M. Herbert (R)(KIA), S/Sgt James H. Lentz (TG)(KIA), S/Sgt Mathias A. Kuffel (BTG)(KIA), S/Sgt Roy C. Loken (LWG) and Sgt Michael J. Halpin (RWG).

|

S/Sgt. Philip Cascio, ball turret gunner on the ill-fated mission of the Spook recalled:

This is an account of events of the last mission of a B-17 bomber named Spook. Our Group, the 303rd's 358th Squadron, was leaving on the Group's 16th mission. We were briefed to depart at 0745 and to return at 1330 - an approximate five hour mission. Most February days in England were foggy, dark, damp, cold, and lonely.On returning after dropping bombs on our target, the St. Nazaire submarine pens, we were nearing the English Channel. Over the interphone, Pilot Dunnica called to our attention a B-17 about 15,000 feet below being attacked by ME-109 fighters. He asked if we wanted to go to their aid. We all agreed. Later, as a POW, I met the members of that bomber. They were from the 306th Group.

We left our formation at approximately 25,000 feet, descended, and circled the crippled bomber at approximately 10,000 feet. From a pack of 5 ME-109s, 15 ME-109s accumulated in seconds. Some of the members of the crippled bomber bailed out, leaving us to face the worst that was to come. Being close to the French coast and the English Channel, we tried to make it back to the base at Molesworth. We were eventually shot down and crashed twenty miles from the English coast in the English Channel. During that part of the air war, we had no fighter escort whatsoever. On crashing in the water, our plane broke into parts. Tail Gunner Taylor went down in the tail section. I feel he was shot and killed before we crashed. Waist Gunner Dew was last seen floating in the high waves of the English Channel. I (Cascio) was able to get out of the ball turret and crawl to the radio compartment. Holland was shot and had blood all over his flight suit. Tucker, upper turret, Co-pilot Pacey, and Cascio escaped through the radio hatch. Of the two dinghies attached to the bomber, only one inflated. We were lucky we grabbed the inflated one. The last I saw of Pilot Dunnica, he was trying to get out of the pilot window. He was pulled down with the front part of the plane.

The three survivors in the rubber dinghies were strafed at least three times. We floated in the bitter cold high waves of the English Channel for approximately fourteen hours. We flipped over many times, pulling each other back to the dinghy by a cord tied to our wrists. We eventually drifted to the coast of Brest, France, in the early dark morning. We crawled to a small hut on the shoreline. Being exhausted, tired, and cold, we slept a short time under leaves and paper to keep warm.

Waking about 0600, we saw a French house in the distance. The French family gave us coffee, bread, and an exchange of clothing--a splendid exchange for them. They made us leave because they were afraid of the German soldiers in the vicinity.

We were captured a few hours later and taken to the Bastille in Paris. All track of time was lost in the tall, dark cell. A few days later, we were taken to Frankfurt, Germany, to an interrogation camp. We then were transferred in a box car to Stalags 3B, 7A, and, eventually, 17B. Twenty-eight months later came the long-awaited end of the war.

Funny, isn't it, how one page can cover two-and-one-half years of a prison life? Seven men from six crews suffered frostbite and burns from defective electric clothing. 1Lt. Donald Stockton, pilot of #41-24610, Joe Btfsplk, 427BS(H), brought his ship back with a hole in the tail assembly "as big as a household door."

The 91BG(H) observed two FW-190s dive on a B-17 formation and drop timefused fragmentation bombs. This was one of the first experiments of this type of Luftwaffe fighter attack.

Maurice K. Selberg, a Paradise, CA resident since 1954, passed away at home on Feb. 2, 2010 with his family by his side. He died of complications from Parkinson's disease.

Maurice K. Selberg, a Paradise, CA resident since 1954, passed away at home on Feb. 2, 2010 with his family by his side. He died of complications from Parkinson's disease.

Born to Swan and Clara Selberg, he requested to be inurned near his parent's grave in Velva, ND. He attended schools in Velva and graduated in 1941. He was a star basketball player, member of the glee club, school band, and formed his own dance band called, "Maurice Selberg and the Blue Moon Orchestra." He met his wife, Cathy at a community dance that summer and continued to date her until their marriage in 1944. They recently celebrated their "65th" wedding anniversary.

Maurice was inducted into the armed services at the age of 21 and served in WWII as a Staff Sergeant on a B-17 bomber as a radio operator/machine gunner for the 8th Air force, 303rd Bombardment Group (H) "Hell's Angels" Combat Team in England.

He attended Minot State Teachers College in North Dakota on the GI Bill and graduated in 1950, majoring in both Business Administration and Education with a minor in Physical Education. His first teaching position (1950-1954) in Judith Gap, MT gave him plenty of opportunities to prove himself. In addition to teaching all of the business education classes, he coached both the girls and boy's athletic teams, directed the school band, and was the advisor for the school newspaper and yearbook. The cold harsh winters inspired Maurice to take his wife, daughter, and son out west to a warmer life in Paradise, CA.

Edward W. "Ned" Schaefer, of Silver Spring MD, passed away December 3, 2009 at Holy Cross Hospital, Silver Spring, MD. A former State Department Foreign Service officer, Mr. Schaefer was 84 years old. He is survived by three sons, Jonathan, Edward and Mason. A memorial service will be held in South Salem, NY, in spring 2010.

Edward W. "Ned" Schaefer, of Silver Spring MD, passed away December 3, 2009 at Holy Cross Hospital, Silver Spring, MD. A former State Department Foreign Service officer, Mr. Schaefer was 84 years old. He is survived by three sons, Jonathan, Edward and Mason. A memorial service will be held in South Salem, NY, in spring 2010.

Schaefer was a waist gunner on the 360th BS Matheson Crew. He was removed from the crew before its first mission in compliance with 8th AF order to reduce the size of combat crews from 10 to 9 men. The Matheson Crew was shot down on their fifth mission (5 KIA and 4 POW). After leaving the 303rd, Schaefer was back in the USA by mid-October 1944 and began training for service on B-29s. By V-J Day he was command gunner on a crew in combat crew phase training in Clovis, NM.

Robert D. "Bob" Stewart, 86, born July 24, 1923 in Endicott, N.Y., surrounded by his family at home, returned home to Jesus on January 26, 2010, after a long battle with cancer. Preceded in death by his daughter Linda Houser, Bob is survived by his high school sweetheart and wife of 66 years, Genevieve; daughter Carol and Ronald Ferrara; son Gregory and Jo Anne Stewart; son Robert and Eileen Stewart; twelve grand-children and twenty two great grandchildren. Robert is a veteran of WWII, serving with the 303rd Bomber Group. He was a technical Sergeant, waist gunner and aircraft medic on a B-17 Bomber. On January 11, 1944 his aircraft was shot down over Germany where he remained a Prisoner of War for eighteen months. Bob was a member (4th Degree) of the Knights of Columbus, Braden Council #5604; a member of the American Legion, Kirby Stewart Post #24; a Post Commander of the Manasota Chapter of Ex-POW's; and a Life Member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and Disabled American Veterans.

Robert D. "Bob" Stewart, 86, born July 24, 1923 in Endicott, N.Y., surrounded by his family at home, returned home to Jesus on January 26, 2010, after a long battle with cancer. Preceded in death by his daughter Linda Houser, Bob is survived by his high school sweetheart and wife of 66 years, Genevieve; daughter Carol and Ronald Ferrara; son Gregory and Jo Anne Stewart; son Robert and Eileen Stewart; twelve grand-children and twenty two great grandchildren. Robert is a veteran of WWII, serving with the 303rd Bomber Group. He was a technical Sergeant, waist gunner and aircraft medic on a B-17 Bomber. On January 11, 1944 his aircraft was shot down over Germany where he remained a Prisoner of War for eighteen months. Bob was a member (4th Degree) of the Knights of Columbus, Braden Council #5604; a member of the American Legion, Kirby Stewart Post #24; a Post Commander of the Manasota Chapter of Ex-POW's; and a Life Member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and Disabled American Veterans.

Daniel T. Deitch, 88, passed away December 13, 2009.

Daniel was born and raised in Chicago; his parents were Russian immigrants, who passed on to him their interest in music and books, and their belief in changing the world for the better. In 1942, Dan volunteered for service in the US Army Air Corps. He was part of the 303rd Bomb Group, of the famed 8th Air Force, stationed in Molesworth, England; a T/Sgt and gunner on the crew of a B-17. He was immensely proud of being part of the Allied forces that fought for freedom.

Daniel T. Deitch, 88, passed away December 13, 2009.

Daniel was born and raised in Chicago; his parents were Russian immigrants, who passed on to him their interest in music and books, and their belief in changing the world for the better. In 1942, Dan volunteered for service in the US Army Air Corps. He was part of the 303rd Bomb Group, of the famed 8th Air Force, stationed in Molesworth, England; a T/Sgt and gunner on the crew of a B-17. He was immensely proud of being part of the Allied forces that fought for freedom.

After the war, the GI Bill gave him the means to go to college, and then medical school, at the University of Illinois. He met my mother in Chicago. As a young doctor, Dad worked hard to bring quality medical care to coal miners and their families in Kentucky and Pennsylvania. The family settled in Detroit for many years, and then moved to Canada. Daniel also lived in Israel for a time, and in New York City. When he retired, he moved back to Toronto, where most of his children had settled. Dr. Daniel Deitch is survived by his wife, 5 children, 2 grandchildren, and one great-grandson. He is buried in Pardes Shalom Cemetery, near Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

" . . . and the planes are empty now . . . "

Robert Gordon Van Antwerp was born on November 8, 1920, in

Oklahoma and passed away on July 15, 2005, in Lake Tahoe. While attending college at Oklahoma University, Robert met the love of his life, Roberta, and after four short months, they eloped. He

received a Bachelor of Science degree in physical education and a minor in business education. In his last year of

college, Robert was the captain of the All-Oklahoma Football Team and received an offer from the Detroit Lions

to attend its football camp as a new recruit. However, a knee injury changed his direction to recreation.

Robert Gordon Van Antwerp was born on November 8, 1920, in

Oklahoma and passed away on July 15, 2005, in Lake Tahoe. While attending college at Oklahoma University, Robert met the love of his life, Roberta, and after four short months, they eloped. He

received a Bachelor of Science degree in physical education and a minor in business education. In his last year of

college, Robert was the captain of the All-Oklahoma Football Team and received an offer from the Detroit Lions

to attend its football camp as a new recruit. However, a knee injury changed his direction to recreation.

In 1944, During World War II, Robert was a bomber pilot and squadron commander with the USAF. He piloted a B-17 for 35 heavy bombardment missions over France and Germany totaling 207 hours of air time. On his 24th mission, he was shot down where upon he was given two weeks rest leave in Edinburgh, Scotland. Being shot down was an adversity that Robert persevered, and he continued to pilot 11 more missions.

After returning to Oklahoma, Robert coached football and taught in Edmond. In 1947, Robert and his wife Roberta moved to Long Beach, California where his first job was as playground director at Houghton Park. Four years later, he was promoted to assistant district supervisor. His full-throttle energy and positive attitude led him to ascend through the ranks until becoming director of parks and recreation. Robert put countless hours in civic and community services. In addition to involvement with the City's Emergency Preparedness Program (as the Chief of Welfare Services), he was active on the Disaster Committee for the American Red Cross. He was a member of the National Parks and Recreation Association and the California Parks and Recreation Society.

His love of people guided him into square dancing. He was an internationally known square dance caller,

one that was inducted into the Square Dance Callers Hall of Fame, an honor only given to a limited amount of

callers. He was known throughout the country as one of the nations most popular and well-publicized square

dance callers. With such a talent, he (with Roberta by his side) instructed over 17,000 dancers. Robert and

Roberta guided dancers on tours throughout 29 countries, 34 states, and many provinces of Canada. His square dance recordings number more than 150 singles and six play albums.

![]()

From 1960 to 1963 Molesworth was where my family lived. My father was stationed at Alconbury. We lived in what was called "tobacco housing" because that's how the US paid for it. My school was in the headquarters building and actually, my fifth grade class in the command room. The map was still up on the wall but covered with peg board because it was considered secret. We used to play in the bomb shelters and machine gun nests. Or in my case, fall through the snow into a bomb shelter, because the snow was so deep. We went to the base chapel. It was our home. My father did over thirty years in the Air Force, from WWll to 1974. Plus my brother and served in the Air Force. Molesworth has a place in our hearts, we are glad someone cares. We did have a friend who passed away recently who we understand did around 50 missions. It would be great to hear from you. I now serve with the Commemorative Air Force, and love it.Keeping the Legacy Alive,

Thank you, Larry Crawford

|